Thomas Floyd’s service to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources as a wildlife biologist spans decades, and his research on the elusive amphibian now fuels statewide ecological awareness efforts.

Thomas Floyd was in fifth grade in 1987, and he was already interested in natural resources. He took a hunter’s education course—a requirement to receive a hunting license at the time—at the Walton Fish Factory, now home to the Wildlife Resources Division. He remembers his father, Don, telling him he might someday work for the Department of Natural Resources. “I scoffed at it and told him that I thought he was wrong,” Floyd said, “and turns out, he was very right.”

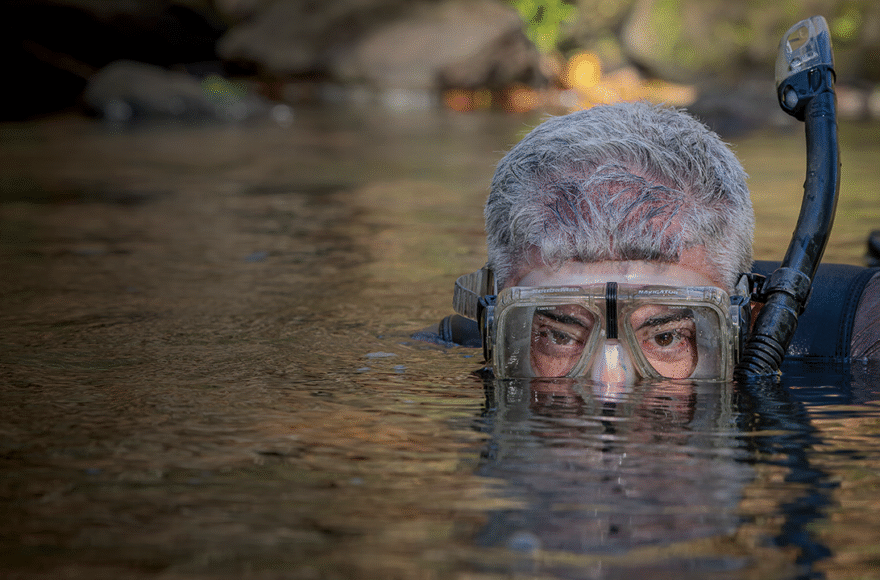

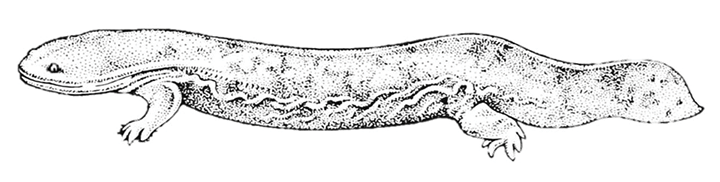

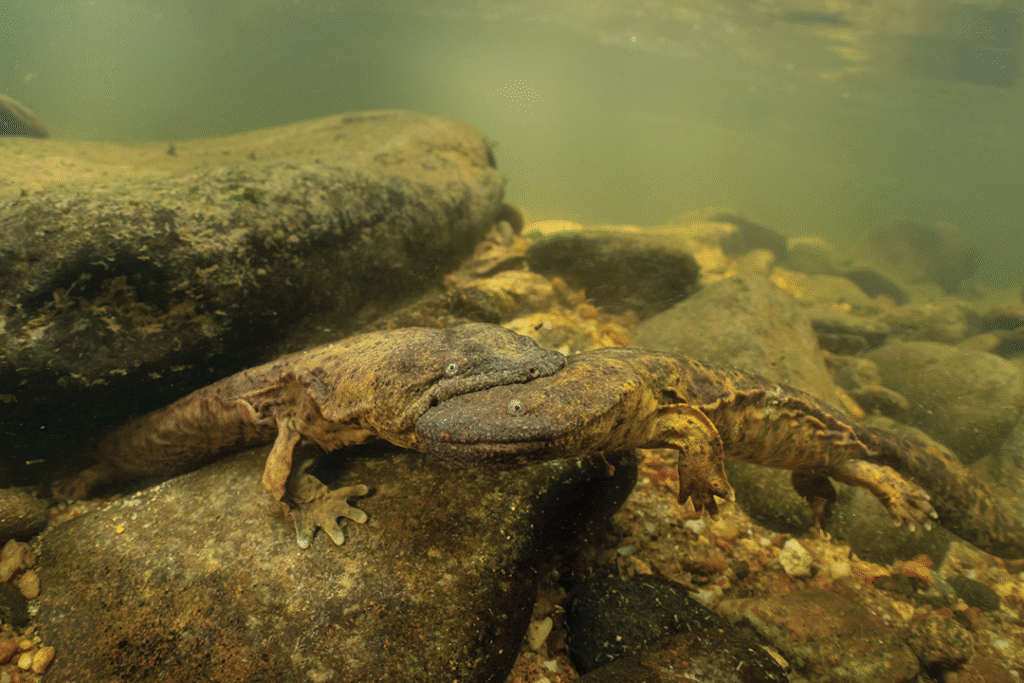

Floyd now finds himself 23 years deep into his role as a wildlife biologist for the DNR. One of his specialties involves amphibians and conservation of individual imperiled species. More specifically, Floyd studies and works with hellbender salamanders, the largest salamander in North America. Completely aquatic and with permeable skin, it is affected by pollutants. Floyd compared it to an “aquatic canary in a coal mine, if you will, for aquatic ecosystems.” Cool, clean, clear, well-oxygenated waters in shade are the characteristics of the environment in which hellbender salamanders thrive. Typically, in Georgia, they can be found alongside trout. There are ways to maintain such conditions, according to Floyd.

“Water, river or stream buffers are key to maintaining healthy populations or healthy water quality through reduction in sedimentation and other inputs of other pollutants,” he said.

Floyd became interested in the hellbender salamander while completing his undergraduate degree from the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forest Resources. He took a natural history of vertebrates class that examined subjects from birds and small mammals to fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Thus, he continued exploring his fascination as part of his graduate degree studies at Clemson University, researching salamanders and other herpetofauna, reptiles and amphibians. The lack of data for the hellbender intrigued Floyd, too. “That’s really the impetus for initiating a long-term monitoring project for hellbenders: to develop a data set so that we’ll be able to have something to compare abundances and population statuses in the future with what we currently have today,” he said.

“It’s just an incredible species to work with, and every time I capture one, I have a period of fascination while it’s in hand.”

Thomas Floyd

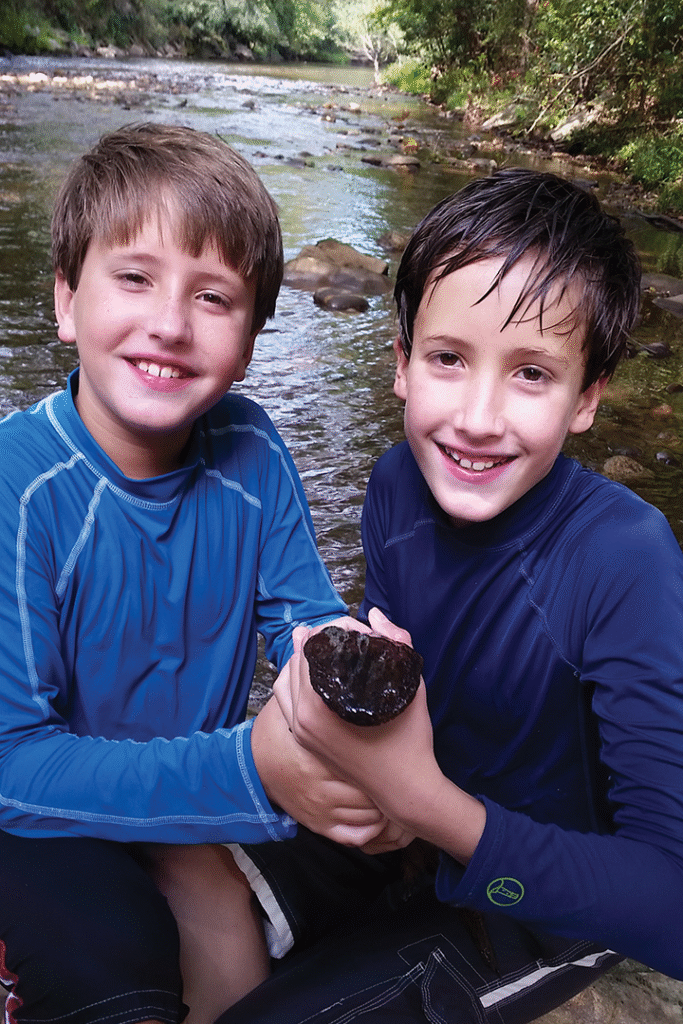

Several initiatives are underway concerning Floyd’s study of the hellbender salamander, one of them the result of a surprise encounter he had during his research. As part of the hellbender survey protocol, Floyd charted a particular stretch of stream that he had studied a handful of times prior to the summer of 2024. In that study, Floyd uncovered just the third documented occurrence of finding mud puppies—three of them, to be exact—along with hellbenders. “It’s odd to think when you’re surveying for something as rare as a hellbender that you could find something that’s probably considered to be [rarer], at least in Georgia,” Floyd said. Following that discovery, an initiative was launched to install signage in portions of North Georgia that includes diagrams of hellbender salamanders and mud puppies to gather information from the public. Floyd believes finding mud puppies and hellbenders to be more common than many realize. “Occasionally,” he said, “I would think a mud puppy or a hellbender is caught on the end of a fishing line, and those are important observations.”

Some additional observations by Floyd: Hellbenders in Georgia are on the smaller end of the size range, and they undergo metamorphosis. Currently, Floyd is studying museum records and specimens from across the range while comparing them to findings in Georgia. He is also working on a manuscript to include adequate information to draw a definitive conclusion and publish a paper on the subject.

Floyd graduated from Newton High School as part of the Class of 1994, its final graduating class as the only high school in the county. Nothing about his upbringing especially influenced his decision to pursue a career path in wildlife biology, besides his involvement in Boy Scouts. However, Floyd admitted he was “ignorant” concerning the significance of his hometown to wildlife. In fact, Floyd did not recognize until after his career began that he played in the same dry Indian Creek that Charlie Elliott once did. “It is ironic that Charlie Elliott is from the same area,” Floyd said, “and he’s so eminently important to wildlife conservation in the state.”

Much has transpired in Floyd’s life since his father foreshadowed his career with the Department of Natural Resources. In addition to his studies at Georgia and Clemson, Floyd became a certified wildlife biologist through The Wildlife Society in 2012. He has now invested more than two decades with the DNR. Nevertheless, Floyd remains enthralled with the hellbender salamander and embraces every encounter with the unique amphibian.

“It never gets old to find a hellbender,” he said. “It’s just an incredible species to work with, and every time I capture one, I have a period of fascination while it’s in hand. That’s plain and simple how I’ll characterize it.”

Click here to read more stories by Phillip B. Hubbard.