As a 19-year-old in World War II, John Burson saw the worst of humanity on the beaches of Normandy, France. In the decades that have followed, the longtime Newton County resident has maintained an unwavering commitment to community service.

World War II was the most tumultuous event of the 20th Century, an epic battle between good and evil during which incredible citizens that contemporary Americans have come to know as The Greatest Generation stepped forward and—through horrific tribulation and sacrifice—saved not only this nation but the entire world from peril.

Millions served in the armed forces, from the day the United States became involved on Dec. 7, 1941 to the final surrender of Germany and Japan in 1945. The estimated total cost in human life around the globe in WWII exceeded 54 million. To put that figure in perspective, it would have equaled the combined population of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Alabama and Mississippi in 2015.

Not long after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a teenager from what was then extremely rural Walton County determined to do what he considered right and noble. However, his parents were not enthusiastic about his plans to enlist in the military and asked that he instead wait until he was drafted. John Burson was not quite 19 years old at the time, but by coincidence, a trusted friend was home on furlough.

“My parents told me to wait, that when Uncle Sam needed me, he would surely call,” Burson, now 95, said. “I ran it by my buddy, and he agreed that I should wait, and he gave me some advice which I followed to the letter, and it stood me well throughout the war. That advice was one, never ever volunteer for anything, two, never complain about anything, [and] three, do your best at whatever you’ve been assigned to do.”

“I had only hoped for two things…one was that I not be drafted in the winter when it was cold, and the other was that I would train in a warm climate. So naturally, I was drafted in the dead of winter, and my training base was … Battle Creek, Michigan.”

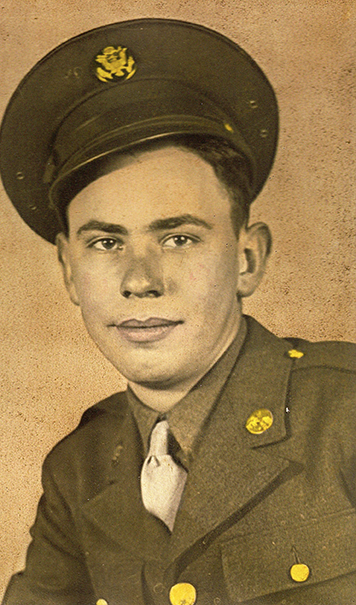

John Burson

The draft notice called Burson to report to Atlanta’s Fort McPherson one year later in January 1943. “I had only hoped for two things,” he said with a chuckle. “One was that I not be drafted in the winter when it was cold, and the other was that I would train in a warm climate. So naturally, I was drafted in the dead of winter, and my training base was … Battle Creek, Michigan.” Assigned to the 428th Military Police Escort Guard, Burson was trained specifically to guard prisoners of war, and his unit’s first assignment was guarding Italian POWs in Indiana. It was quite different from what awaited him in Europe, as the Italians were content in comfortable quarters with good food in the safety of America’s Midwest.

Easter week 1944 saw the 428th ship out to Bridgewater, England. The erstwhile Battle of the North Atlantic had by this time seen the near-complete elimination of Germany’s U-boat threat to shipping, so the trip was pleasant.

“We were among the last units to board a converted passenger liner,” Burson said, “so we were berthed near topside in the comparatively roomy areas. It was a smooth voyage.”

As England was bursting at the seams with American troops in the buildup for the Operation Overlord invasion of France, Burson was lodged with an elderly English couple with a spare bedroom. Admonished not to drink their tea or eat their cookies—rationing for the Brits was strict—he tried to invent reasons to decline their repeated invitations for “a spot of tea and a scone.”

“Finally,” he said, “the gentleman told me quite sternly that he would not be offering if he did not mean it, so from that day on, I learned how to properly have ‘a spot of tay,’ as they pronounced it, with them.”

On June 6, 1944, Americans drew the worst assignments of the five beaches in Normandy, France. It was D-Day. Omaha and Utah were bloodbaths. Not counting the wounded, allied dead totaled 4,404. It was into this scene that Burson disembarked from his landing craft the next morning. Nothing had prepared him for what he witnessed.

“The first thing I saw was a leg sticking up from a boot,” Burson said, “and then, on the beach, the bodies of the boys were stacked like cordwood.”

The 428th was immediately attached to the U.S. 29th, which had borne the brunt of a vicious defense. Burson’s formidable task was to escort German prisoners from the battles raging inland to the beaches and load them for transport to England. It was not an easy mission, as these were not Italians enjoying their time in Indiana. As the Allied forces made rapid progress, the 428th became attached to the 1st Army, 5th Corps, 5th Armored Division. When the Germans left Paris, Burson rode in the parade down the famed Champs Elysees before taking more German POWs into custody. The 5th Armored later liberated the country of Luxembourg, and Burson’s unit was there. Before orders slowed them down, they crossed the Mosel River into Germany. Politics were at play and halted the Allied advance.

As his unit arrived in Belgium to rest and refit, Burson received a rare 48-hour pass to Paris. He had not requested it but gladly accepted. “A friend of mine who had been in our unit with me the whole way had been turned into a clerk typist,” Burson said, “and when six passes to Paris were allocated to our unit, he put my name on one of them.” It took two days to reach Paris. Then the 48-hour pass began, followed by a two-day trek back to Belgium. “We got off the truck,” Burson said, “and were handed a helmet and a rifle and told that there was no such thing as a non-combatant unit now, for the Germans had broken through our lines.”

The Battle of the Bulge had begun. When the bloodiest battle in Europe was over, Burson’s unit was sent to the Germany-Czechoslovakia border to marshal German POWs. However, the toughest assignment was still to come.

“When the war was over, we were sent into Russia to safeguard the German POWs and regular soldiers back to Berlin,” Burson said. “The Nazis had committed such atrocities against the Russian population during their drive to Stalingrad in ’42 that unescorted Germans were being set upon by the Russian civilians and slaughtered wholesale on the spot, so it was our task to get them safely back through Russia and Poland to Berlin.”

At long last, as the demilitarization process took time, Burson in December 1945 embarked at LeHavre, France, aboard a ship destined for Newport News, Virginia. It was no passenger liner, and the dead of winter in the North Atlantic was not a pleasure cruise under any circumstances. However, they reached the United States, and although there was no hoopla like the celebrations photographed in other harbors—see New York—Burson was just glad to be home.

“We got off the truck and were handed a helmet and a rifle and told that there was no such thing as a non-combatant unit now, for the Germans had broken through our lines.”

World War II veteran John Burson

Discharged from the Army on Dec. 15, 1945, he could not wait to return to Walton County and a $15-a-week job at a furniture store. However, the Army veteran’s circumstances changed. Burson was offered a job with the telephone company that paid a whopping $31 weekly, and he met a young woman named Ruth, who became the love of his life. They relocated to Newton County in 1951 and settled in Oxford, where in 2019 they will celebrate an incredible 72 years of marriage. Along the way came three children, four grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

“As important as John’s wartime service was and is,” Ruth said, “I really believe what he’s done after the war bears mentioning, too.”

Burson’s desire to serve did not end on the day of his discharge. In the decades that followed, he helped organize the Volunteer Fire Department of Oxford and became a charter member of the Oxford Lions Club, which sponsored the creation of the Covington’s Lions Club and Scout Troop 221 in Oxford. Burson served as Scoutmaster for Troop 221 and continued to work with the Boy Scouts for decades. In addition, he performed prodigious work cataloging the Oxford Historical Cemetery and served on the Newton County Board of Education in the locally tumultuous time of the late 1970s and early 1980s, helping guide the school system toward the excellence status enjoyed today.

Burson can truly be considered a man for all seasons, even as he ponders other paths.

“I tell you,” he said with a laugh and an air of seriousness, “on that voyage home from LeHavre, the Atlantic was so rough they had to keep all of us below decks with the hatches battened down, as the sea was breaking over the deck. I was sick as could be, but on the third day, the sea calmed and we were allowed topside for some air. Just as I got to the rail, I saw a passenger ship appear heading due east to France, and I tell you, the sea had been so rough, if I thought I could’ve jumped overboard and made it to that ship, I’d be a Frenchman today.”

Fortunately for the people of Newton County, he came home instead.

Click here to read more stories by Nat Harwell.