Anderson Wright rose out of a segregated Oxford to build a life through steadfast resilience, dedication to family and his transformative experiences in the United States Navy. Now in his late 80s, he remains engaged in civic life, education and preserving local history.

Anderson Wright was born in Oxford on June 19, 1936. Nearly nine decades later, the octogenarian still calls the city home. Some of his earliest memories are of his father, who died when Wright was just 4 years old. Soon after, Wright and his sisters, Catherine and Grace, moved into his grandparents’ house in the Oxford neighborhood known as “Texas.”

Wright loves reminiscing about his childhood, of carefree days spent running barefoot outside with his friends, inventing games and grabbing snacks from the blackberry bushes and fruit trees that grew in their neighborhood. He attended elementary school at Oxford’s Rosenwald School, one of approximately 5,000 schools built in the rural South to provide educational equity for African American children. The Tuskegee Institute’s Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, a philanthropist and president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., collaborated to make education more accessible to all. The son of an immigrant peddler, Rosenwald only agreed to fund each school after the surrounding community had invested money in the project, usually through donations and fundraising efforts. Oxford residents answered the call. Though the Oxford Rosenwald School no longer stands, parts of the foundation are still visible beside the historic marker on Mitchell Street. Wright still sees those teachers—many of whom had received degrees from the Tuskegee Institute—as inspirations, as he attended the school from first through eighth grade.

“I rode the bus home from the Rosenwald School, and I had to make sure I got back home on time,” Wright said. “There was a ballpark nearby, and sometimes, we would stop by and stay too long. I remember trying to explain to my grandmother where I’d been, but she knew my friend’s reputation and told me to go get a switch. Well, I didn’t get a switch big enough, so I had to get another one. When I got that whipping, my sister started crying. I asked her why she was crying when I was the one getting whipped.”

Wright remains grateful for his family’s firm discipline and strong work ethic, which molded his character. In ninth grade, he progressed to Washington Street High School in Covington. The institution was founded by his great-grandfather. After graduating in 1954, Wright attended a trade school in Atlanta and worked at Oxford College during the summers.

“People ask me why I would want to move back here when I could have retired anywhere. I tell them that it’s because I knew I could serve and make things better.”

Anderson Wright

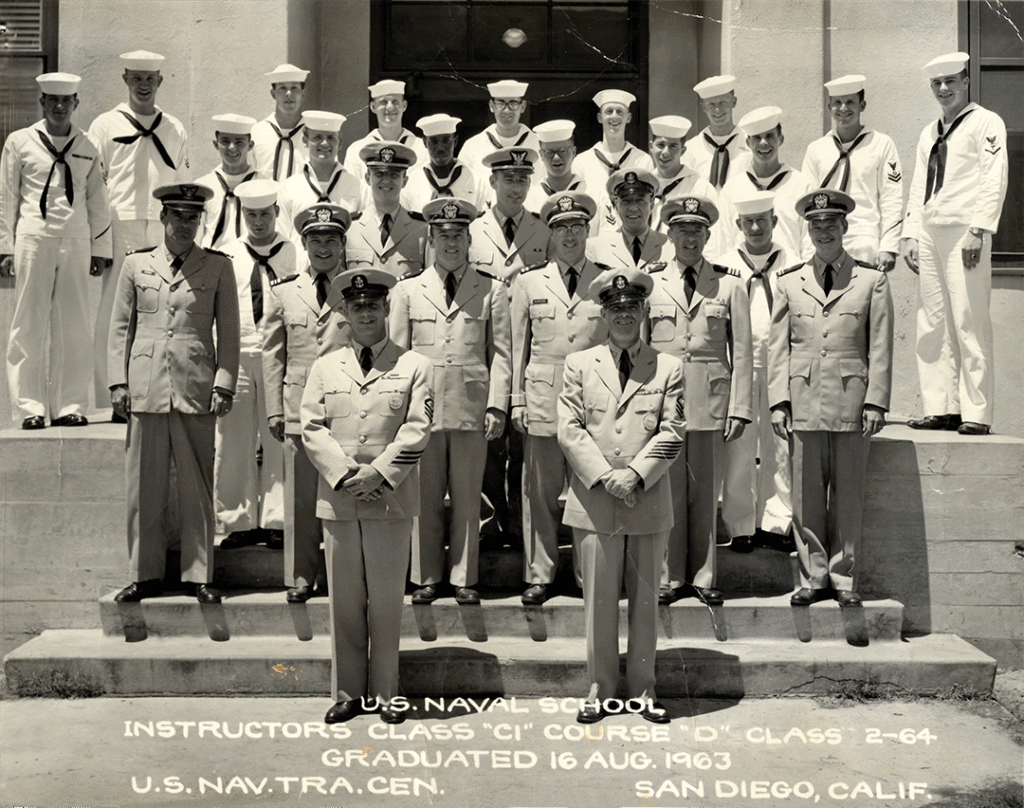

“One day, my high school friend Nathaniel Russell and I decided that we were going into the Air Force,” he said, “but they told us they didn’t have any openings at that time, so we went down the street and joined the Navy instead.” The recruiter told them they could leave as soon as the next day if they passed the test. They did and rode a train to Chicago for boot camp, only to be immediately detoured to another site in San Diego. After boot camp, when tests revealed their individual strengths, Russell was sent to Class A school to become a steward’s mate. “They taught him how to take care of officers, cook for them and shine their shoes,” Wright said. “I did not like the idea of that at all.”

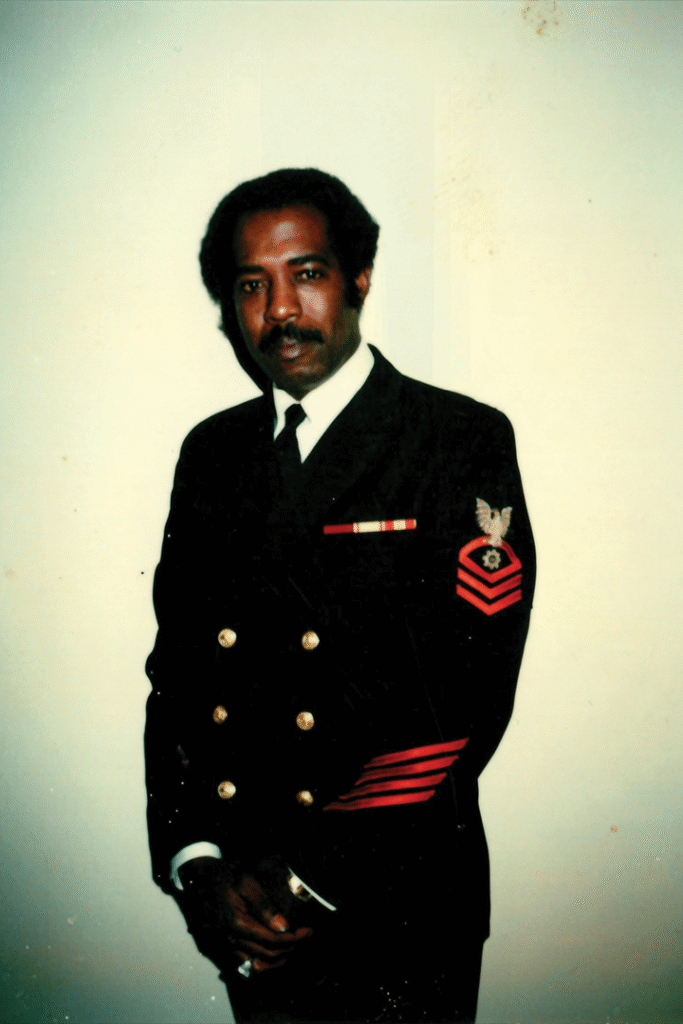

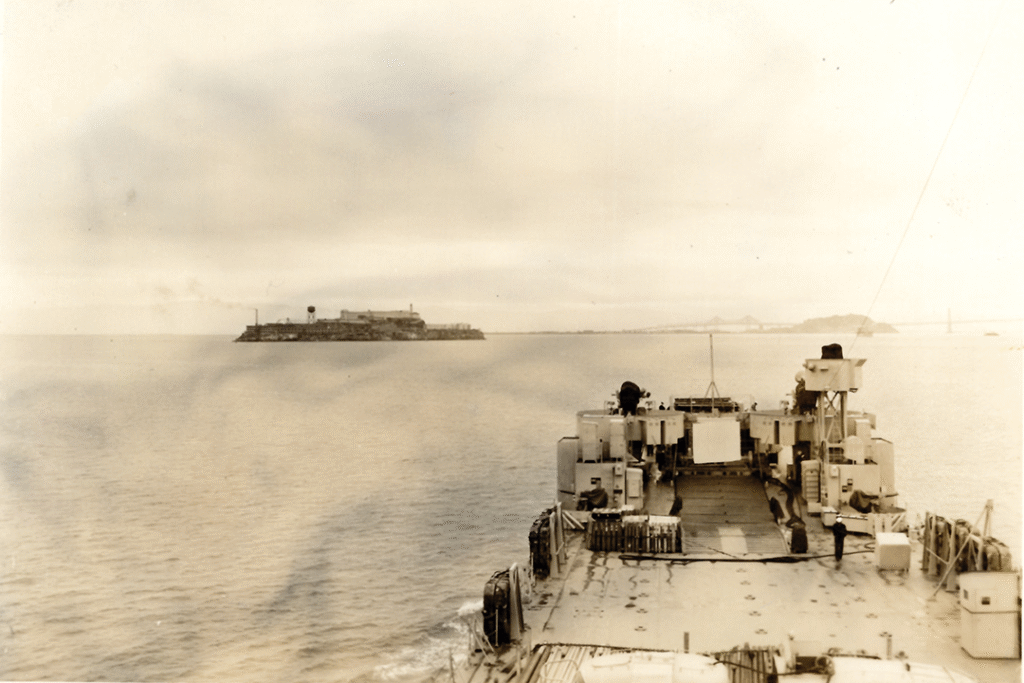

In April 1955, Wright was assigned to the deck crew of LST 1159, an amphibious ship based in San Diego. He was one of only two black sailors aboard. “My job was cleaning the deck, painting and taking care of the machinery on the deck,” he said. Wright remembers painting the ship’s hull one day while sitting on a Bosun chair, when the seat came loose. “I was hanging on the rope when a friend saw me. He was a small, short guy from Greece. He put his hand down and said, ‘Catch my hand!’ I said, ‘I can’t. I’m going to fall!’ He said, ‘You won’t fall. I’m Greek.’ So I reached up, and he pulled me aboard,” Wright said, his voice still incredulous over the small man’s surprising strength. “We stayed in contact for a long time.”

A petty officer in the Engineering Department later extended an invitation to Wright. “He asked if I’d like to work in his department,” Wright said. “Naturally, I said yes, but I asked him if I would be accepted because I would be the only black man there at that time. He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. You’ll be working with me.’” One of Wright’s new duties involved cleaning the ship’s bilges. Wright used the menial task to his advantage, learning where all the color-coded pipes went and what each was used for. His insider knowledge helped him pass the exam to become a Petty Officer 3rd Class Engineman. Wright’s work ethic and drive to learn earned him the respect of his fellow crew members, and he soon progressed to Petty Officer 2nd Class Engineman.

“I did well,” Wright said. “A friend of mine, a career sailor, told me how proud they were of me. That made me feel good. The other black man aboard was also a 2nd Class Petty Officer, and everyone had a lot of respect for him, too. I made good friends throughout the ship.”

In 1956, the ship headed to the Far East, stopping in Hawaii before moving on to the Philippines, several ports in Japan and Korea. “I remember Korea very well,” Wright said. “We picked up soldiers from there. That’s what our ship was about: transport, tanks and soldiers. We also had space to transport one helicopter.” He enjoyed multiple trips between San Diego and the Far East during the remainder of his four-year service contract. “Then I had a big decision to make,” Wright said. “Reenlist or get out.” He chose to exit active duty and join the Navy Reserves, while using his GI Bill to study diesel and gasoline engineering. Later, he took a job as a mechanic and decided to attend Los Angeles City College, where he majored in business and police science. When he graduated in 1969, he pursued further education in industrial science at California State University, Los Angeles.

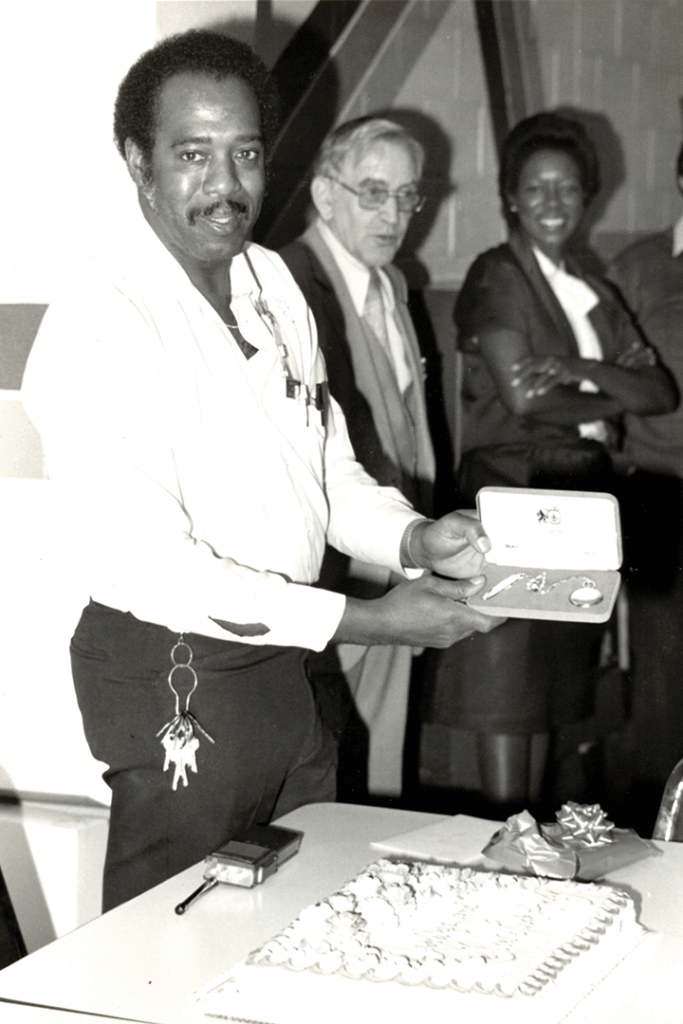

Over the next few decades, Wright’s life took several turns. The United States Postal Service hired him as a temporary holiday season mechanic. He then passed the carrier/clerk exam and continued working in that role. Later, he moved on to become a mailbox mechanic and a mail flow mechanic. “That involved fixing equipment like belts, motors and sorting machines,” he said. “A lot of it was electronics, which used my Navy experience.” True to form, Wright was promoted to higher levels and became a supervisor. In all, he worked for the USPS for 37 years before he retired.

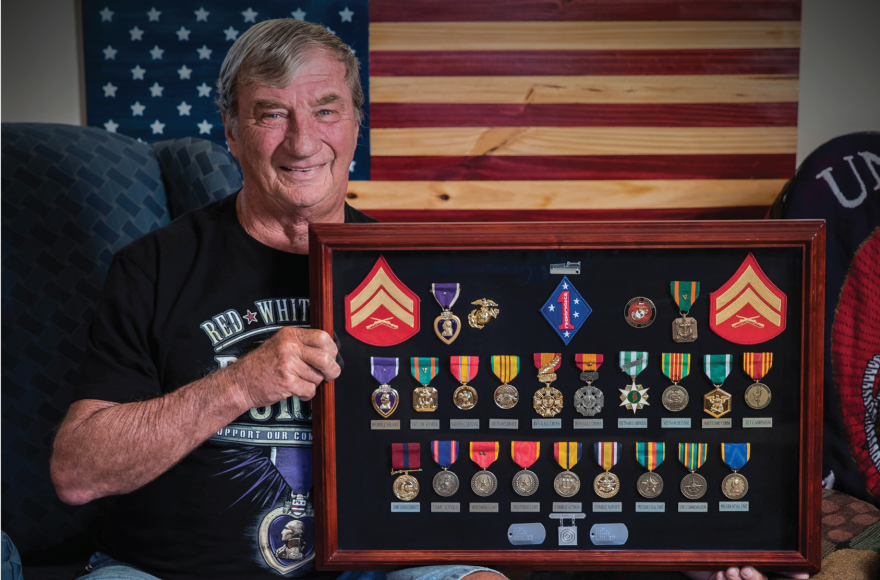

Wright also continued to serve in the Navy Reserves, training one weekend a month and for a longer period each year while advancing to Chief Petty Officer. He recalls returning to Los Angeles in 1965, after spending two weeks on ship duty. “We had heard about the L.A. riots on the radio, but we thought they were exaggerating,” he said. “Then we got back, and they said over the PA system to be careful, that the National Guard was patrolling the streets and there had been many fatalities. I didn’t really see all the damage that had been done until I was driving home.” Wright retired from the Navy Reserves on June 19, 1996.

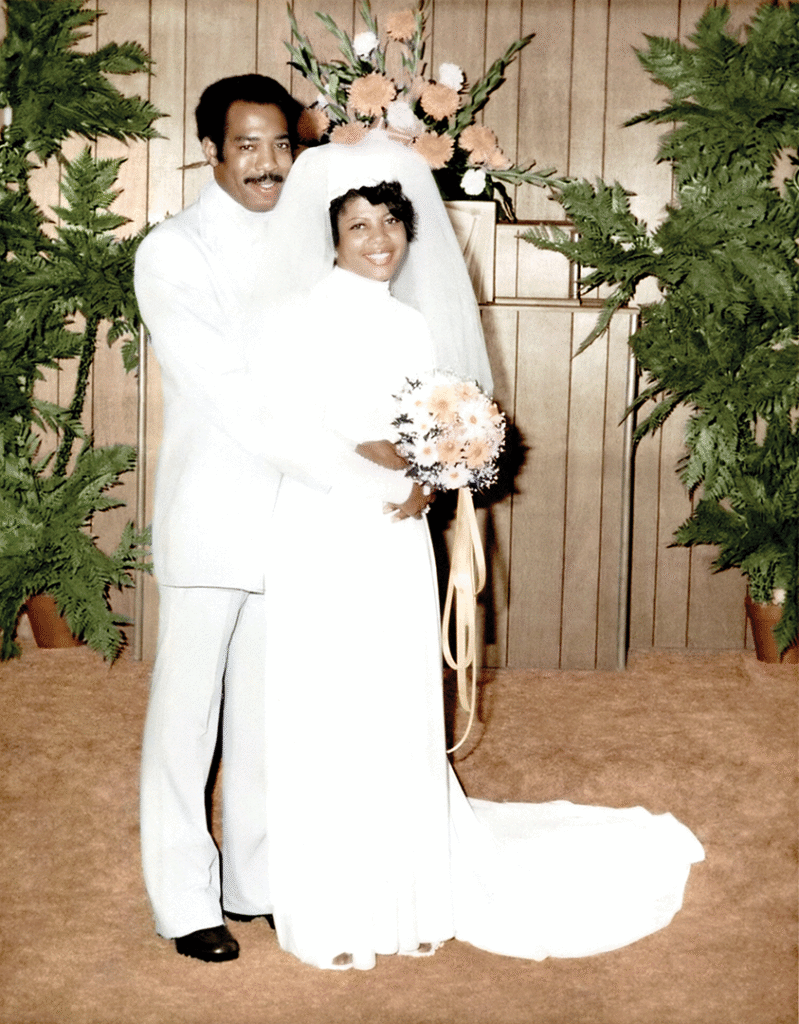

Wright always maintained a strong connection with his family in Oxford and even built a small home in which to stay while visiting. His first marriage was brief and ended in divorce but not before he was blessed with two sons, Kelvin and Andray. Years later, he met the love of his life, Mary Ann Brinson, while they both worked at the post office. They married in 1976 and had two daughters, Davetta and Rava. Once the Wrights had retired from the postal service, they returned to Oxford permanently in 2008 and built a larger home. Wright returned to his childhood church, Rust Chapel UMC on Emory Street, and became a Sunday School teacher. He also began attending city hall meetings and joining service organizations, including the Lions Club, where he enjoyed providing disadvantaged children with new bikes and participating in various community service projects. Much of his work has been focused on the Oxford Historical Cemetery Foundation, where he now serves as president. Wright finds joy in keeping busy with all the organizations and his church, but he admits that sometimes he lacks the energy to work at his accustomed pace. He has battled prostate cancer since 2019 and outlived the doctors’ prognosis.

“My daughter keeps asking me to cut back, but I really don’t want to,” Wright said. “I grew up during segregation. I remember the KKK coming through Oxford, but I’ve seen so many encouraging changes. People ask me why I would want to move back here when I could have retired anywhere. I tell them that it’s because I knew I could serve and make things better. I’ve always tried to do that. I am still trying to do that.”

Click here to read more stories by Kari Apted.