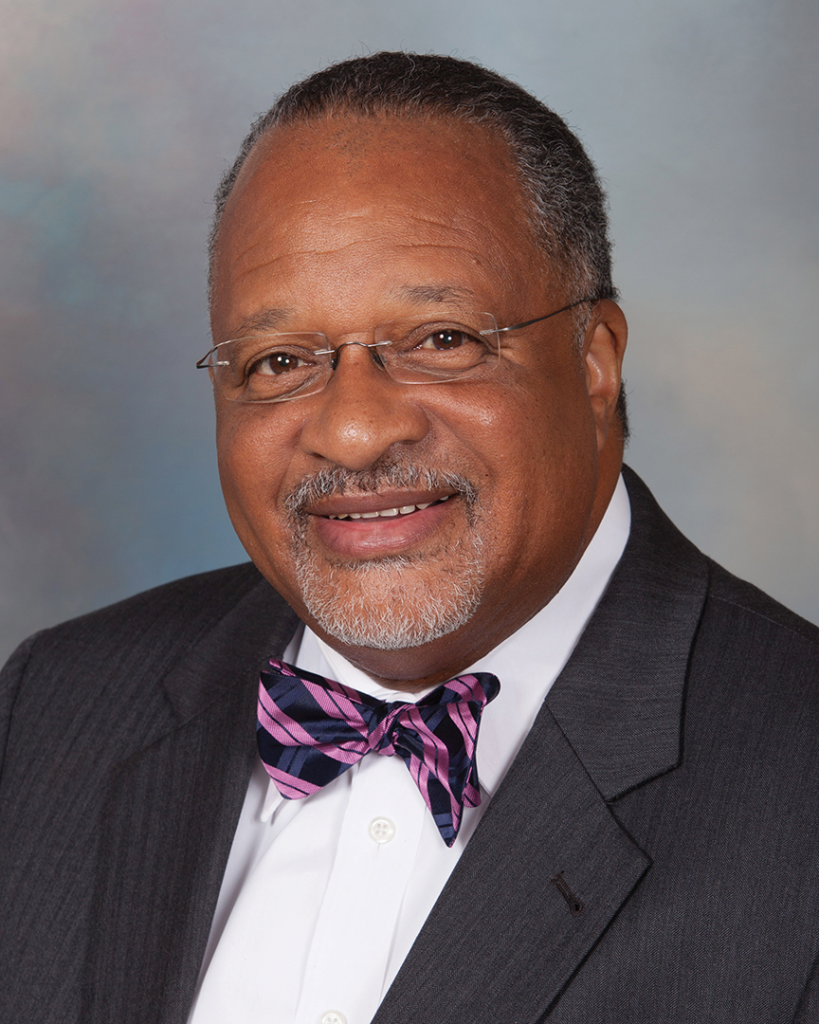

The tragic death of former Covington assistant police chief and Newton County school board representative Almond Turner in 2019 left a lasting void in the community he faithfully served for decades, but for those who were closest to him, his indelible legacy endures through the countless lives he touched.

A year to the day after Almond Turner’s death, it felt no less surreal for those closest to him. No less heartbreaking. No less like an awful nightmare from which one tries to wake. That was how Turner’s son, Dwahn, described the day that he and others gathered around his father’s final resting place to pay tribute to a life that had been inexplicably snuffed out by a family member’s gunfire 365 days earlier in Meridian, Mississippi.

“It just still doesn’t seem real,” Dwahn said. “It doesn’t feel like we should even be here.”

Perhaps that was because there are still so many unanswered questions surrounding Turner’s death. News outlets reported that Christopher Denson—Turner’s nephew—left a birthday party on the night of Nov. 23, 2019, retrieved an AK-47 from his vehicle and returned to fire some six shots, striking and fatally wounding the former Covington assistant police chief in the head and chest.

Typically in such cases, more information begins to trickle down to the victim’s family after a few weeks or months pass: details like motive, a plea or a trial date and word on possible punishment. All of it helps to provide a semblance of closure. A year later, however, the Turners had experienced no such relief.

“He was the best man at my wedding. We played golf together. We talked. We shared. Now, when life hits me, I do feel lost, like I don’t have anywhere to go. You can’t give the trust you have for your father to anyone, and that generates a sadness that I still feel.”

Dwahn Turner

“It’s been tough on all of us,” Dwahn said, “and we’re still trying to make sense of why it even happened. We don’t have any answers, and the COVID-19 pandemic stuff has really slowed that process down in Mississippi. We’re still reeling because we don’t have any idea what happened or what took place to even trigger such an event.”

Dwahn revealed there was some speculation about Denson’s mental health, that perhaps he had some schizophrenic tendencies that might explain his deadly outburst. While it remains something of a mystery, the situation could have gotten much worse had Denson’s brother not wrestled the gun away from him.

“I’m not sure that my dad was really the target,” Dwahn said.

The impact of Turner’s death extends far beyond his immediate family. His absence from the Covington Police Department, the Newton County School Board and the community as a whole has only highlighted his importance and strengthened his legacy.

“His presence is still being felt, and honestly, that’s why it hurts like it does,” said Covington Police Chief Stacey Cotton. “It’s what everybody knows about Almond. It’s the humanity that came out of him, the smile, the positive mental attitude he had about everything. He was always a glass-half-full guy, and no matter what the situation was and no matter what was coming against him, he was always positive. Not only is that mindset contagious, it’s also rare.”

Cotton first met Turner in high school. However, he was granted his first real glimpse of his larger-than-life persona when he, not Turner, was promoted to assistant chief.

“He took me to get my polygraph test when I first came on [with the police department],” Cotton said. “When I’d gotten promoted, some folks had some hurt feelings. Even Almond came to me and said he was sort of hurt that he didn’t get [the job] but that he’d do everything he could to help me be successful, and he never left me. When I became police chief, he was the first person [to whom] I turned to promote. His loyalty and willingness to put emotion aside was astounding.”

Cotton depended on Turner to help him bridge generational and ethnic gaps—something that proved beneficial, given the nationwide tensions between police departments and people of color.

“We were obviously born in two different generations and in two different races,” Cotton said. “I was born in 1965 in the height of the Civil Rights movement, but everything I knew about it was taught to me in school. Almond lived it, and he could sit there and talk to me personally about his struggles and he could put it on a level to where you could understand it, causing you to recognize the plight of the African American community that many didn’t know. I use those things every day now in my personal and professional life.”

Turner was not always straight-faced and serious. Newton County School Board representative Shakila Henderson-Baker appreciated his softer and lighter sides.

“I knew Mr. Turner and his family since I was a little girl. We lived seven houses down from them, so I grew up knowing that family,” she said. “He was a mentor to me, and I saw him through many roles, but one thing I loved about him is that he was a comedian. He always loved to make people laugh. He’s somebody that you couldn’t tell sometimes whether he was being serious or not. He’d tell you something, let you think about it and then come back and say, ‘I’m just messing with you.’”

Henderson-Baker recalled a story Turner often relayed about his wife, Anita, and their first date. Turner had issued a challenge to himself for the benefit of his future bride, claiming he could put an entire apple in his mouth. When he tried to do so, Henderson-Baker remembered what happened through his own words: “The doggone apple got stuck.”

“We were all at a conference eating dinner together when he told this story, and his wife was just sitting there eating her salad, not flinching, and said, ‘He’s not kidding,’” Henderson-Baker said. “He told us the apple had to be cut out of his mouth, and after Mr. Turner finished telling the story, his wife followed up and said, ‘And I still married him.’”

Henderson-Baker also admired how Turner’s rugged exterior— the kind typically associated with a career law enforcement professional—did not prevent him from being in touch with his emotions.

“He was a big crybaby,” she said, choking back a sob with a laugh. “That’s something I didn’t always know. One time, during one of our Teacher of the Year celebrations, we had a guy who was from Louisiana, and he talked about Hurricane Katrina and growing up in the New Orleans area, the crime and violence and how he lost some friends along the way. It was really impactful. I was crying, and Almond leaned over to me and asked, ‘Are you crying?’ Next thing I know, he reaches out a hanky because he had tears rolling down his eyes.”

Drawing back the curtain and revealing a little more about their friendship, Cotton concedes that he and Turner often took turns pulling the emotions out of each other.

“We’d often choke each other up,” he said. “One time at an event, I started talking about our department, and whenever that happens, I’d get a little emotional; and when I started to cry, he’d start to cry. The joke around the department was that we were ‘The Crying Chiefs.’ People would say, ‘Y’all two can’t talk without getting choked up.’”

Cotton and Henderson-Baker feel an immense void, professionally and personally, because of Turner’s absence. Even after his retirement, Turner still made his presence known. Cotton admits it will always be difficult knowing his co-worker, friend and trusted confidant will never walk through the door of his office again. Henderson-Baker can still hear Turner’s voice of reason as she goes about her work, but she concedes it will never compare to his actual company. Dwahn feels a different kind of emptiness. In his father’s stead, he felt an immediate need to assume the mantle of leadership in his family. That has proven exceedingly difficult without the man on whom he leaned for direction. Such shoes are impossible to fill.

“When life stuff happens, Dad was the one I went to talk to,” Dwahn said. “He was the best man at my wedding. We played golf together. We talked. We shared. Now, when life hits me, I do feel lost, like I don’t have anywhere to go. You can’t give the trust you have for your father to anyone, and that generates a sadness that I still feel.”

Dwahn also draws on his father’s commitment to faith as an example. Turner made certain his family attended church regularly to study God’s word and to gain an understanding of the importance of prayer. It anchors Dwahn today, inspires him to try to carry out his father’s legacy and led to the establishment of the Almond James Turner Foundation. During the 2020–21 school year, it will provide three scholarships to local students—one each to Newton, Eastside and Alcovy high schools.

“We want to continue the legacy of protection and service for community concerns,” Dwahn said. “We want to do it in his name.”

The foundation will be just one of many ways the people who knew Turner best ensure he will be remembered by those to whom he dedicated his life.

“I think if you’re reading his story and you know him well, I can’t tell you anything anyone else doesn’t already know,” Cotton said, “but for those who didn’t know him, all I can say is I’m sorry. I feel sorry for the people who didn’t get to know Almond Turner, because if you knew him, you’d have no other choice but to love him.”

For more information on the Almond James Turner Foundation, visit AJTFoundation.org.

Click here to read more stories by Gabriel Stovall.