Experience in the military and at Delta set the stage for Covington-based Aerodox founder David Burk’s entry into the business of Minimum Equipment Lists—manuals that inform crews about how to make airplanes airworthy when certain systems are not functioning properly.

David Burk, the founder and CEO of Aerodox, gathers his employees for their weekly meeting every Monday morning. The first items on the agenda are always the same: prayer and recommitting the company to God. It serves as Burk’s reminder that his plans are written in sand, and God’s plans are what count.

You could say that aviation is in Burk’s blood. His father was in the Air Force and his mother worked for Cessna when they met, and he was born at McConnell Air Force Base in Wichita, Kansas. His family moved a bit with the Air Force—stops included Arkansas and Germany—and his young life was a little messy. His parents divorced and his mother remarried a couple times, but at a crucial point, Burk found himself on a Texas ranch, where his tinkerer’s itch was scratched and nurtured.

“I was 13 years old, and I had a blast,” he said. “I went hunting and fishing, got to drive a tractor [and] work cattle.”

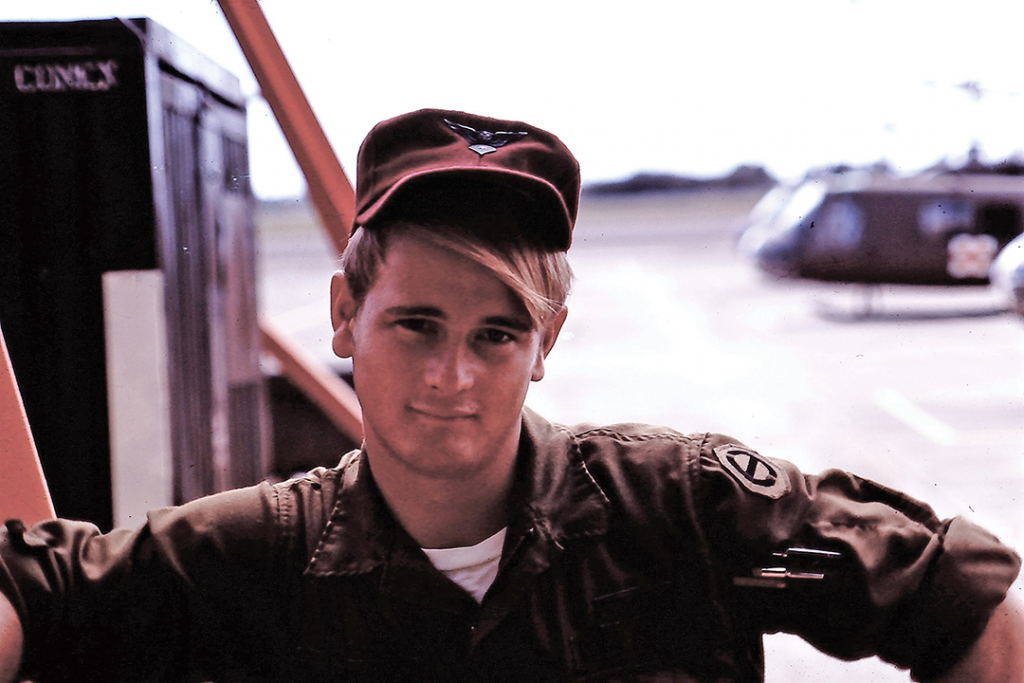

Always the kid who liked to take stuff apart, Burk explored the mechanical world in earnest. By the time he finished high school, Burk and his mom moved back to Arkansas. The Vietnam War was still raging, and Burk was set to enlist in the Air Force when his father suggested that he go into the Army instead because he would make rank faster. Taking his father’s advice, Burk went off to basic training at Ft. Polk, Louisiana, in August 1971. “We were actually one of the first basic training groups that went through that was all-volunteer,” he said. “The drill sergeants weren’t sure how to treat us.” Burk was sent to Ft. Gordon in Augusta to train as an avionics mechanic, fully expecting that he would be sent to Vietnam to work on Huey helicopters after graduation. God had something else in mind.

“I love what I’m doing. Nothing turned out like I planned, and that’s a good thing.”

Aerodox CEO David Burk

“Every two weeks, they graduated a class and 95 percent of that class went to Vietnam,” Burk said. “My class graduates, they posted our orders and every one of us were going to APO 96557. We looked at each other and asked, ‘Where is that?’ Vietnam was 96225.’” They asked their sergeant, who looked it up and told them: Hawaii. The Army was pulling its aviation assets out of Vietnam, slowly preparing for the end of the war. Burk missed going to Vietnam by two weeks. “I was assigned to the 68th Medical Detachment, [part of the 25th Infantry Division], which was a helicopter ambulance unit,” he said, “so half our unit were aircraft with bullet holes in them. The others were new.”

Instead of repairing Hueys for battle, Burk received another assignment: Using the medical evacuation experience from Vietnam, he and others would partner with civilian emergency services to create something called Military Assistance to Safety and Traffic units.

“We had to come up with Standard Operating Procedures,” Burk said. “We had to figure out how to talk to the ambulance, fire department and police. Who does what when we fly civilians? Where do we take them?” One day Burk’s superiors walked into his shack and handed him a hand-held Motorola radio with an order: “Burk, install this in the Huey.” He answered, “Where? How?” They told him he would have to figure it out, so that was what he did. Little did he know that it was pretty much what he ended up doing for the rest of his career, just not for the Army. The MAST unit was a great success, and Burk was awarded the Army Commendation Medal for the work he did there. Most importantly, MAST units paved the way for air ambulances that are commonplace in communities worldwide.

Burk enjoyed his time in the military and intended to make it a career, but his marriage and the arrival of three daughters altered those plans. After three years in Hawaii, they were sent to Ft. Riley, Kansas. Promotions for avionics mechanics dried up. He would have to make a hardship tour to Korea, so it was time to move on. In February 1979, Burk went to work for Delta, and he and his family moved to Atlanta. Working in avionics, his specialty, Burk spent time on all the concourses at what is now Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and a few years at the maintenance control center, which is where he was introduced to creating Minimum Equipment Lists, the business in which he finds himself today. An MEL is a manual that informs crews and maintenance teams about the steps to take to make an airplane airworthy, or legal to fly, when certain systems are not functioning properly. Obviously, the engine has to work, but other items that do not affect the plane’s ability to fly can be worked around.

“A simple example are the red and green lights on the wingtips,” Burk said. “If those aren’t working, can you fly? The regulations say, yes, you can fly during the daytime. They are not required. The MEL would read: ‘The position light may be inoperative, provided you don’t fly at night.’”

Burk was going to teach maintenance of the MD90, a new plane Delta had just bought. The Friday before training was to start, “someone” discovered there was no MEL. Burk was asked to pull a team together to write the MEL, get it published and approved by the Federal Aviation Association by the time the plane went into service in six weeks. They did it. Burk and his team also came up with a proprietary way of creating the MELs, including the pilot’s procedures from the maintenance manual in the MEL.

“When Delta saw it, they realized they needed a group,” Burk said. “They got six of us together and formed an MEL group. We produced all the MEL texts for Delta in the new format, which they still use today. That’s how I got into the MEL business.”

Burk and three colleagues formed their own company in December 1999 to create MELs for small airlines or independent aircraft owners who did not have an MEL group. Initially called Dispatch Deviation Consulting, Inc., Burk bought out his partners by 2006, when he took early retirement from Delta. By then, he had changed the name of the company to Aerodox. The family business was growing steadily. Burk added employees, including two of his three daughters, Cheryl and Kristen.

“The game plan is for Kristen to take over my position,” Burk said. He encouraged her to get her pilot’s license, and she accompanies him to quarterly FAA Industry Group meetings in Washington. “She’s in the room on those discussions, so she can get the tribal knowledge.” Aviation remains a man’s world. “There are usually just one or two women in those meetings at the most, but she can hold her own,” Burk said. “She will do great.”

In 2018, Aerodox moved its offices to the Covington Municipal Airport. Fittingly, there are windows on three sides so Burk and his employees can see when planes arrive.

“I love what I’m doing,” he said. “Nothing turned out like I planned, and that’s a good thing.”

Click here to read more stories by Patty Rasmussen.