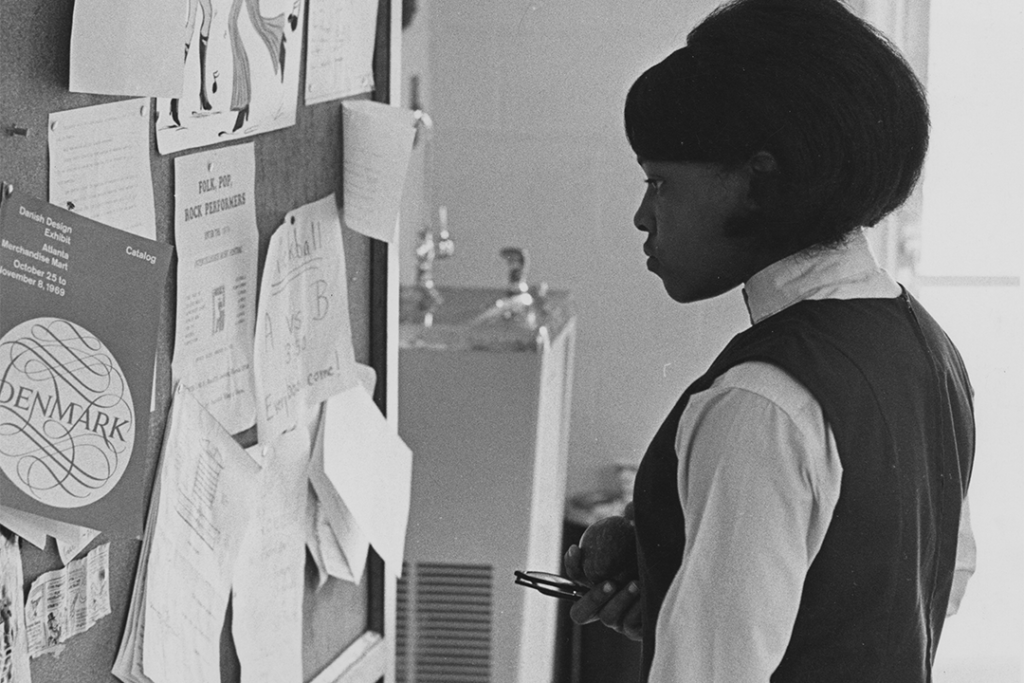

Jack Simpson served under legendary FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and was assigned to several historic cases during his remarkable law enforcement career, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“‘They call me Mr. Jack,’” he said simply. It is a title of endearment and well-earned respect. Jack Simpson is 96 years old and widely recognized as the oldest active law enforcement officer in the country. Thirty years after the age when most peers are easing into retirement, Simpson still reports for duty three days a week as an investigator with the Newton County Sheriff’s Office. In the process, he informs and inspires appreciative associates as he shares insight and perspective from seven decades of law enforcement experience, including investigating such high-profile cases as the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination.

“Mr. Jack is a wealth of knowledge,” said Newton County Sheriff Ezell Brown, Simpson’s boss and close friend. “I would describe him as a walking history book.”

Although Simpson claims he was merely “lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time,” he admits it all began with a youthful dream that he was determined to follow. “Through my childhood—the FBI, the ‘G-Men,’ the guys with the Tommy guns—they were my heroes,” he said, referencing icons from the Prohibition Era of the 1930s. “I made up my mind as a little kid that someday I wanted to be an FBI agent.” Nothing, not even a World War, would keep him from reaching his goal.

Jack Byron Simpson was born in the small coal-mining town of Barnesboro, Pennsylvania, in 1924—the same year J. Edgar Hoover was appointed director of what is now the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Growing up in the lingering shadow of The Great Depression, Simpson worked his way through high school and upon graduation landed a clerical job with the FBI as a fingerprint classifier. However, he was not yet an agent. A degree in law or accounting was a prerequisite for the position at the time, and with no money for college, Simpson’s dream remained out of reach. He had managed to get his foot in the door, but as other doors opened to promotional opportunities within the bureau, he saw them close just as quickly.

“I had something hanging over my head,” he said. “I had ‘1-A’ as my status in the draft.”

“When I worked in the civil rights period, black and white didn’t mean anything to me. If you’re a decent human being and you’re doing right and trying to make a contribution to society, you’re my kind of folks.”

Newton County Sheriff’s Office Investigator Jack Simpson

World War II was in full swing, and Simpson’s superiors at the FBI were reluctant to invest time and money training someone who might be called into military service. “After a while, I got tired of this,” he said, “and I decided the only way out of this maze is to volunteer.” After being turned down by the Navy due to color blindness, Simpson enlisted in the Army and was sent to Camp Butner, North Carolina, for training. “I never had anything like a cushy job after that,” he said. “I became a combat infantry soldier.”

Like many of his generation, Simpson was reticent to elaborate on the details of his accomplishments during the war, providing only a matter-of-fact summary. As a light artillery gunner during the invasions of southern France and Italy’s Anzio Beach, Simpson distinguished himself for “bravery and meritorious service” while earning two Bronze Stars.

The war ended with Simpson having survived its horrors. Back home, he picked up where he had left off, relentlessly pursuing a career as an FBI agent. Utilizing the newly passed GI Bill, Simpson poured himself into his studies and earned a bachelor’s degree, then his master’s. He had been working as a teacher for about five years and was in his first year of law school when an inspector from the FBI took notice of Simpson and encouraged him to take the qualifying test to become an agent. He took the test, passed it and, as the saying goes, the rest is history.

As a special agent, Simpson played an important role in a number of landmark civil rights cases in the 1950s and 1960s. One of the most notable was what came to be known as “The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.” Gov. George Wallace had defied federal law and a court order by prohibiting the racial desegregation of the University of Alabama. On June 11, 1963, the governor blocked the door through which Vivian Malone and James Hood sought to enter and thereby become the first black students to successfully integrate the previously all-white school. Simpson was part of a group of FBI agents whose job it was that day to scan the volatile crowd for those who might violate the law.

Even as he focused on the job at hand, Simpson knew he was witnessing history. “Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katsenbach stood at the door,” he said. “Gov. Wallace stood at the door.” Both men were flanked by law enforcement, as Katsenbach told Wallace he was being ordered by the President of the United States to step aside. Wallace, however, stood his ground and interrupted Katsenbach with a speech about states’ rights. Finally, after a tense, hours-long standoff, it was over. Wallace took a step back and equal rights for African Americans took one big step forward. Simpson summed up the day’s momentous events: “A young lady, Vivian Malone, and a young man, James Hood, integrated the University of Alabama peaceably.”

Unfortunately, not all of Simpson’s cases were as free from violence. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968 was perhaps the most notorious. Simpson reflected on King’s vision and the prophetic words he spoke just one day before his death. “He said that he had climbed the mountain and he looked over and he saw the Promised Land, and he might never get there himself, but his people would,” he said. “James Earl Ray killed him with a shot from a rifle.” When Ray’s 1966 Ford Mustang turned up at a housing project in Atlanta following the shooting in Memphis, Tennessee, Simpson was one of the agents who searched it for evidence. Afterwards, he was tasked with personally carrying that evidence to the FBI lab in Washington, D.C. Ray was ultimately arrested and charged with King’s murder.

Of all the civil rights cases he worked, Simpson may have played his most crucial role in the Lemuel Penn murder investigation. On the fateful night of the crime, Penn and two other black men, all WWII veterans, were returning home to the nation’s capital after participating in Army Reserve training in Fort Benning. Simpson described an all too pervasive scene in the South at the time. “Klansmen were parading around in their robes, threatening and intimidating people,” he said. “Penn was worried about that, so they traveled a back road to get back to Washington.” Early in the predawn hours of July 11, 1964, they stopped their car in downtown Athens to switch drivers. Three Klansmen were watching and noticed their Washington, D.C., car tag. “[One of] the Klansmen said, ‘There goes some of President Johnson’s boys, come down here to agitate and destroy our way of life,’” Simpson said. “They followed Lemuel Penn and his cohorts out of town, and when they got to the Broad River Bridge, they pulled up alongside, fired two shotgun blasts into the car and hit Lemuel Penn in the throat and killed him.”

Simpson was one of several agents assigned to investigate the brutal murder. From a list of known local KKK members, Simpson and his partner drew the name of James Lackey. “We followed him around,” Simpson said. “We learned his routine, we learned about his background, family—everything.” Once the agents felt they had enough information, they approached Lackey to interview him. “He denied knowing anything about the murder,” Simpson said, “or having anything to do with it.” Unconvinced, Simpson and his partner persisted and interviewed Lackey again a week later. This time, they procured the confession that broke the case.

“He’d been sick,” Simpson said, “and I said to him, ‘James, you’ve got something that’s bothering you; something’s on your conscience. I think you want to tell us about it. You might feel better.’ And he blurted out, ‘Well, I’ll tell you. I drove the car.’ And he named the two guys—[Howard] Sims and [Cecil] Myers—that had fired the shotguns. I got the signed statement from him.”

A full account of the incident was captured in Bill Shipp’s book, “Murder at Broad River Bridge.” An excerpt from the historical marker at Broad River Bridge notes that “the case was instrumental in the creation of a Justice Department task force whose work culminated in the ‘Civil Rights Act of 1968.’”

Simpson’s dream job as an FBI agent spanned 23 years and ended in 1978 but not before he landed an assignment he never could have envisioned, not even as a child. As an agent in the Correspondence and Tour section of the bureau, one of his duties was to compose letters for the director. “I was the little kid who admired J. Edgar Hoover and his ‘G-men’ way back when,” Simpson said, “and all of a sudden, here I am in Washington, D.C., working for my hero and writing letters for him.”

Simpson continued his career in law enforcement after his time in the FBI, serving the next 35 years as a bailiff, first with Rockdale County and then with Newton. For the past several years, he has been a part-time investigator with the Newton County Sheriff’s Office, where he does most of his investigative work with a phone and a computer. He also teaches diversity classes to deputies as part of the block training at the department. Drawing from personal experience, he sometimes addresses law enforcement and veterans groups. In his spare time, he writes a weekly newspaper column, choosing topics he hopes will inform and help his readers.

“I think you need to be busy in life with a purpose,” said Simpson, who has seen his children and grandchildren follow in his footsteps and become public servants themselves. As he nears the century mark, he may have slowed down but sees no reason to quit. “I can’t imagine sitting on a porch somewhere wondering what the day is going to hold for me.”

Once turned down by the Navy for his inability to see certain colors, he readily admits to another kind of color blindness.

“When I worked in the civil rights period, black and white didn’t mean anything to me,” Simpson said. “If you’re a decent human being and you’re doing right and trying to make a contribution to society, you’re my kind of folks.”

“Murder at Broad River Bridge” is available for purchase from The University of Georgia Press.

Click here to read more stories by David Roten.