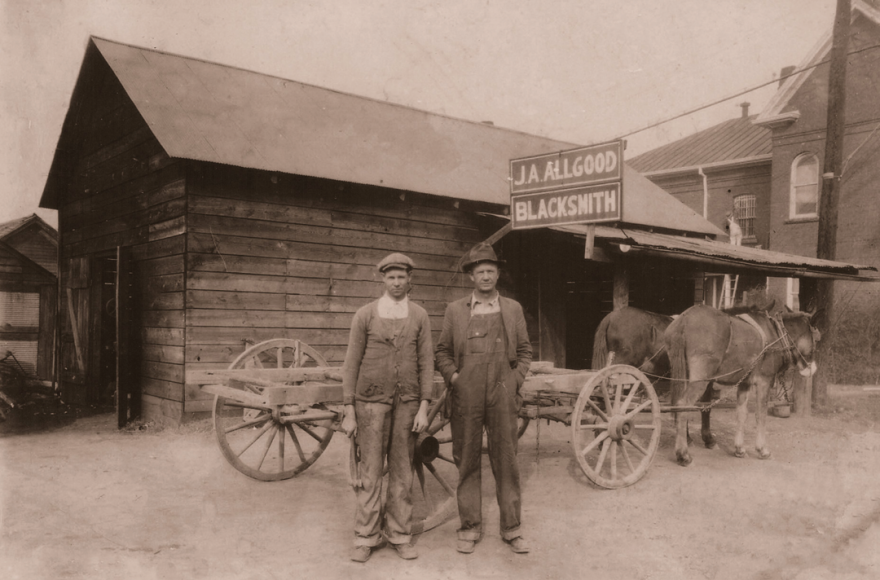

Jobe Addison Allgood owned and operated the last-known blacksmith shop in Covington until his death in 1967. The memories that were made there remain ingrained in those who knew him best, including the grandson who idolized him.

by Bobby Hamby

Jobe Addison Allgood was a blacksmith, a husband and a father—and he was my grandfather. He owned and operated the last true blacksmith and wheelwright shop in Covington. He did it all, from shoeing horses to sharpening iron, repairing plows and building and repairing wagons and wagon wheels. He was born in Jersey on Aug. 25, 1895, the fifth of seven children. His father was a farmer and a blacksmith, and as Jobe grew up, he learned all aspects of farm life, from planting and harvesting to building and repairing farm equipment. His father also taught he and his brother the skills of a blacksmith and wheelwright.

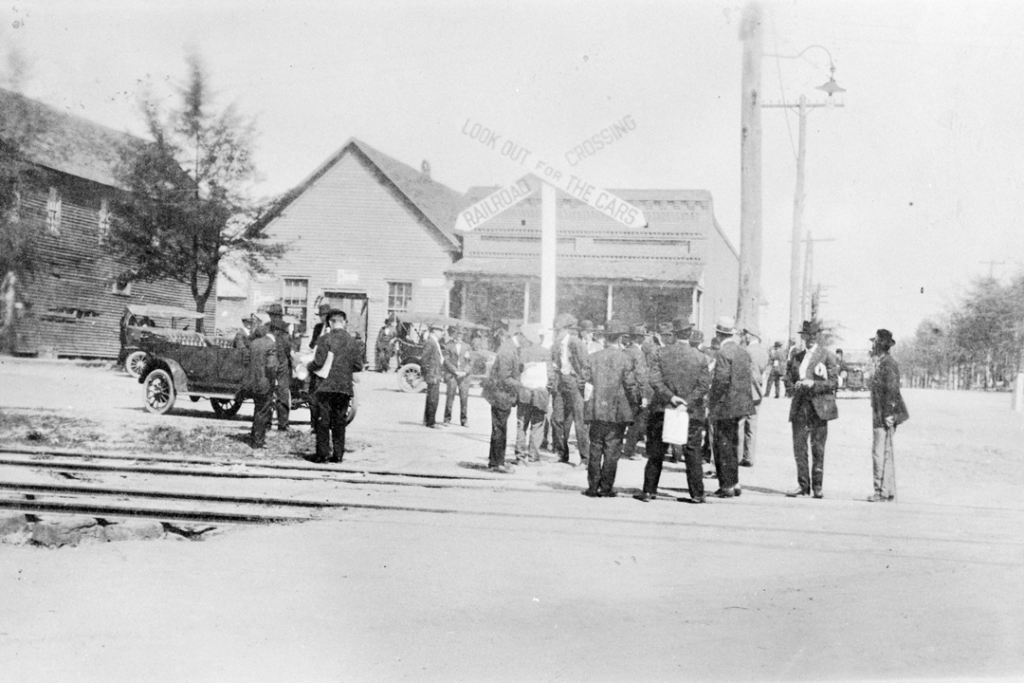

My grandfather met the love of his life and married Martha Melvina Lawhorn in August 1914. They had three children, including Lizzie May, my mother. Sometime before 1917, they moved to Porterdale, where he worked at the cotton mill for the Bibb Manufacturing Company. They relocated to Covington in the 1920s, and Jobe worked for a blacksmith on Hunter Avenue. Between 1895 and 1919, there were as many as four blacksmiths in business on that short street.

Jobe opened his first blacksmith shop around 1927 at the corner of Hunter Avenue and Stallings Street, two blocks from The Square. It was across from the old historic jail. Seven or eight years later, the shop was relocated about 100 feet or so up Hunter Avenue to a building that once housed a blacksmith in the 1800s. By that time, Jobe’s was the only blacksmith shop in town. They dismantled his old facility and used the materials to enlarge his new location. That shop was next door to Meadows Dry Cleaners, where the new judicial building now stands.

I spent a great deal of my youth in that shop, and I tell everyone that 90% of all I know was learned there. Jobe—we called him Pa—was a kind man who was admired and respected by all who knew him. Friends and customers fondly called him Mr. Joe. Looking through his old ledgers from the 1950s and 1960s, it reads like a veritable Who’s Who of Newton County. These were the people who shaped this community into a great place to live. People often asked Pa why he chose not to charge more for the services he performed. “They have to feed their family, too,” he answered. That was one of many do-the-right-thing lessons I learned from him.

“People often asked Pa why he chose not to charge more for the services he performed. ‘They have to feed their family, too,’ he answered. That was one of many do-the-right-thing lessons I learned from him.”

Bobby Hamby

A man named Lewis Wright worked in the shop until the day my grandfather died. He was always working on something, and as he struck the red-hot metal with his hammer, you could hear the ring of the anvil all the way to The Square. On one particular day that I will never forget, Lewis was shoeing a mule. I stood in the doorway to the shop, and my grandfather walked up to talk to Lewis. All at once, the mule turned his head, reached over and bit Pa on his shoulder. My grandfather drew back and hit the mule right between the eyes. It staggered a bit and fell to its knees. Lewis fell over backwards. I stood there with my mouth agape, not sure of what I had just witnessed. My grandfather was in his 60s at the time and knocked a mule senseless. I can only imagine how strong he must have been in his younger years. Lewis started laughing, and I followed suit. The mule slowly returned to an upright position, and Pa mumbled something as he retreated back into the shop.

Lewis lived in a small room in the back of the blacksmith shop. That was the one place I was forbidden to go, although I did have a glance a time or two when the door was open. It had one small window, a bed, a table and a chair. Lewis’ brother, Henry, was a tattoo man in the circus. He had tattoos all over his body. When the circus was not on the road, he stayed with Lewis at the shop. How they stayed together in that tiny room remains a mystery. Henry often received postcards from circus buddies, and his best friend was Emmett Kelly, the world-famous clown. Kelly sent a card every week or two. I had no idea who he was until I saw “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Henry put the postcards on the wall at the shop. It was covered with them, and I am sure they were still there when the building was demolished.

I was the luckiest kid in town to have had J.A. Allgood as my grandfather. Whenever I hear the ring of an anvil, it takes me back to those days at the shop. I cherish them. They were some of the best times of my life.