Sanford Stadium, a 93,000-seat shrine to college football in the south, rests at the epicenter of University of Georgia fandom. Though the man whose name it bears was born in Covington a little more than six years after The Civil War concluded, his contributions continue to echo from one generation of Bulldog to the next.

Kole Cotton was 7 years old the first time he laid eyes on Sanford Stadium in person. The date was Oct. 7, 2000, and the Georgia Bulldogs were set to do battle with Tennessee—an opponent they had not beaten in more than a decade. Cotton remembers it like it was yesterday. The sounds. The smells. The pageantry. Most of all, he recalls being greeted by a pulsing red wave, as 86,520 fans poured into one of the nation’s foremost shrines to college football.

“I could not get over how cool it was that I was a real fan of something,” said Cotton, a 2012 graduate of Eastside High School who turned 28 in July. “Our seats were on the south side of the stadium on the 50-yard line, about half way up the lower level. When we got to our aisle and I took a couple steps in and saw that power G on the middle of the field, I was mesmerized. The feelings that came over me in that moment I will never be able to re-create.”

“The size of the stadium was like nothing I had ever seen,” he added. “I could not get over how big it was. On top of that, the sea of red throughout the stadium was so vibrant. It looked like someone had just taken a big red paint brush and painted the whole thing.”

The Bulldogs defeated Tennessee 21–10 behind two rushing touchdowns from Jasper Sanks. Afterwards, thousands of Georgia fans spilled onto the field and tore down the goalposts to celebrate their team’s first win over the Volunteers since 1988.

“When we got to our aisle and I took a couple steps in and saw that power G on the middle of the field, I was mesmerized. The feelings that came over me in that moment I will never be able to re-create.”

Kole Cotton

“I didn’t know fans being on the field was a big deal until my dad said, ‘Pay attention to this. You’ll probably never see it again,” Cotton said. “I started taking mental notes of the stadium. I noticed all the flashes still going off in the stands from people’s cameras.” The once-pristine Chinese privets that ringed the field paid a price, too. The famed hedges had not been spared. “When we made our way to the southwest tunnel to leave, I noticed these bushes were all torn up,” Cotton said. “I thought about the bushes in front of our house and thought, ‘Dad would kill me if I messed up our bushes.’ About that time, I saw my dad walk up to the bush and pull five or six pieces off. I thought he was going crazy. He walked back over to me and my brother and handed us each a piece and said, ‘Y’all got a piece of the hedges.’”

Cotton kept the small piece of broken hedge on his dresser for years, the memento serving as a constant reminder of an unbreakable bond he was forming with the Georgia football program. His story, in some shape or form, likely mirrors those of so many others in this state. At the epicenter of their fandom sits Sanford Stadium, which can now seat more than 93,000 people. However, its deep-rooted local ties are known only to the most ardent UGA supporters.

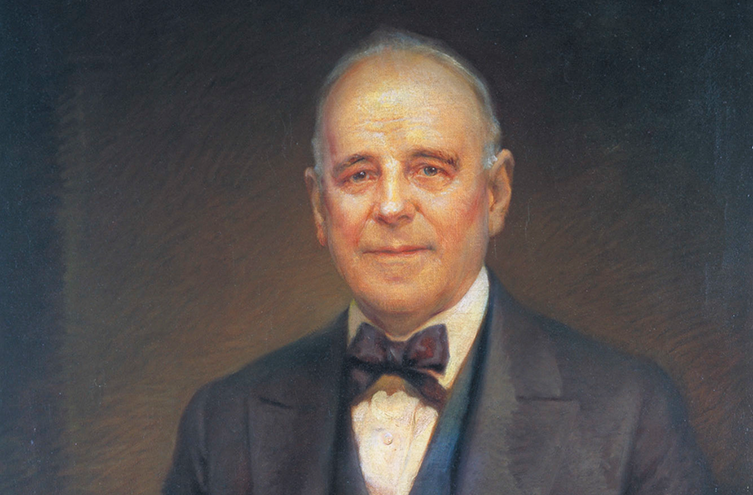

Steadman Vincent Sanford was born in Covington on Aug. 24, 1871 and died on Sept. 15, 1945. The impact he made in those 74-plus years are immeasurable. Sanford accepted a position as an English literature professor at the University of Georgia in 1903, became the faculty advisor to the athletics committee and, in 1911, was instrumental in the decision to relocate the school’s football facilities to a central location on campus. It was named Sanford Field. However, it was too small to accommodate the large crowds that were swarming to rivalry games, most notably Georgia Tech—a fact that forced the two teams to move the game to Grant Field in Atlanta every year. The reality did not sit well with Sanford. After a 12–0 loss to the Yellow Jackets in 1927, he undertook the task of constructing a more appropriate venue in Athens, and a year later, ground was broken on Sanford Stadium. It opened with a seating capacity of 30,000—equal to that of Grant Field—on Oct. 12, 1929 and forever altered the landscape of college football. Subsequent expansions have more than tripled its size.

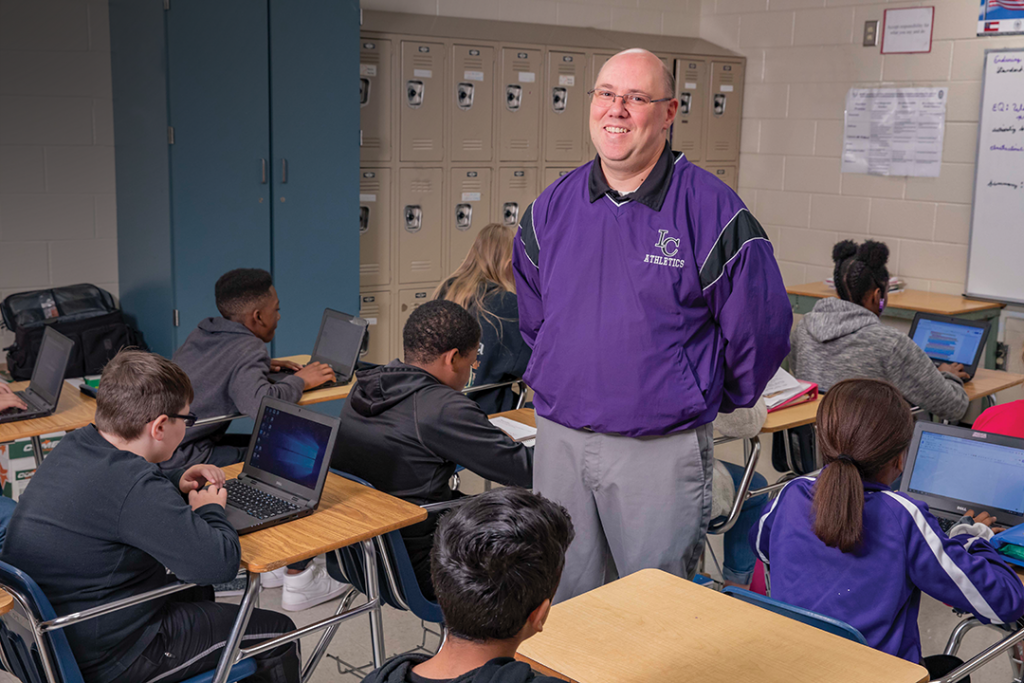

Micah Lacey, the youth pastor at Crossroads Baptist Church in Social Circle, graduated from Georgia in 2016. He attended every home game while he was a student and continues his unwavering support of the school and its football program alongside his father, a season-ticket holder. Vivid memories are ingrained in Lacey.

“When you’re a student, you’re likely to walk past Sanford Stadium every single day of the week, and that just adds to the anticipation of those six or seven home games,” he said. “It’s crazy to think that there’s almost 360 other days out of the year, but those six or seven Saturdays seem to be as significant as the rest of them combined. It’s more than just going to watch a football team play. It’s your school, your classmates, and it’s something that you’re a part of and that’s a part of you and always will be.”

Lacey was 13 when he attended the famous “blackout” game against Auburn on Nov. 10, 2007. Georgia bludgeoned the archrival Tigers in a 45–20 rout, the emotional win spearheaded by 101 yards rushing and two touchdowns from Knowshon Moreno and a pair of touchdown passes from Matthew Stafford. The blackout had been orchestrated by then-head coach Mark Richt.

“He had communicated to the fans during the week leading up that the seniors were asking everybody coming to the game to wear all black, versus the normal sea of red you see at most home games,” Lacey said. “Georgia had never worn or even displayed black jerseys prior to that game, and they came out in warmups touting our traditional home reds. However, when they came through the tunnel to run through the banner—I’ll never forget how it seemed like forever that they held those gates closed—the Dawgs busted out in the cleanest black jerseys you’ve ever seen. The stadium absolutely lost it.”

Click here to read more stories by Brian Knapp.