Imagine ‘Hoosiers’ in a town about 20 times the size of Hickory, Indiana, and stretch it out over about a 17-year period. That was the Newton County boys’ basketball team under legendary coach Ronald M. Bradley.

I quit talking about Newton County basketball 20 years ago, because if you didn’t experience it, you wouldn’t believe it happened. Furthermore, I could tell that when I began to talk about the magic of Rams basketball during the glory days under coach Ronald M. Bradley, everyone who took time to listen started to get that little smirk around the corner of his or her mouth that said, “That’s a good story, and old Darrell is known for good stories.”

As given as I am to hyperbole, I’ve never felt the need to use it when talking about the Newton County High School boys’ basketball team from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. Have you seen the movie “Hoosiers?” First, take “Hoosiers,” extrapolate it to a town about 20 times the size of Hickory, Indiana, and stretch it out over about a 17-year period. Next, throw in Sheriff Henry Odum Jr., complete with cowboy boots and a 10-gallon hat with a diamond-studded star, who led the team everywhere it went for nearly two decades and wasn’t above turning out the lights in the gym if the Rams were struggling or out of timeouts. You also have to remember Mrs. Pearl Young, who sat on the front row dressed all in red. She stood up and put on her red gloves to pronounce victory at the end of close games.

Then there was Archie Patterson, a career Navy man from Porterdale and former professional prizefighter. He sat in the same seat every game for a decade and a half. To make sure nobody took his place, he bolted a stadium seat to his spot just behind the rail, on the aisle, front row and just to the left of the Rams’ bench. Heaven help anyone who dared to attempt to sit in his seat. Remember, he was a prizefighter, and he had the oft-broken nose and disposition to prove it. A few times, wayward fans of a visiting team made the mistake of sitting in Archie’s seat. One look at his face was all it took for them to correct the error of their ways. Archie always carried a .22 pistol wrapped in a handkerchief in his hip pocket. One memorable night, when the Rams were playing Tucker, a fight broke out on the floor, and the stands emptied. Archie was in the process of climbing over the rail in front of him when his .22 dropped out of his pants and went off, shooting him right in the buttocks. With stories like this, I don’t need to make up anything about Newton County basketball.

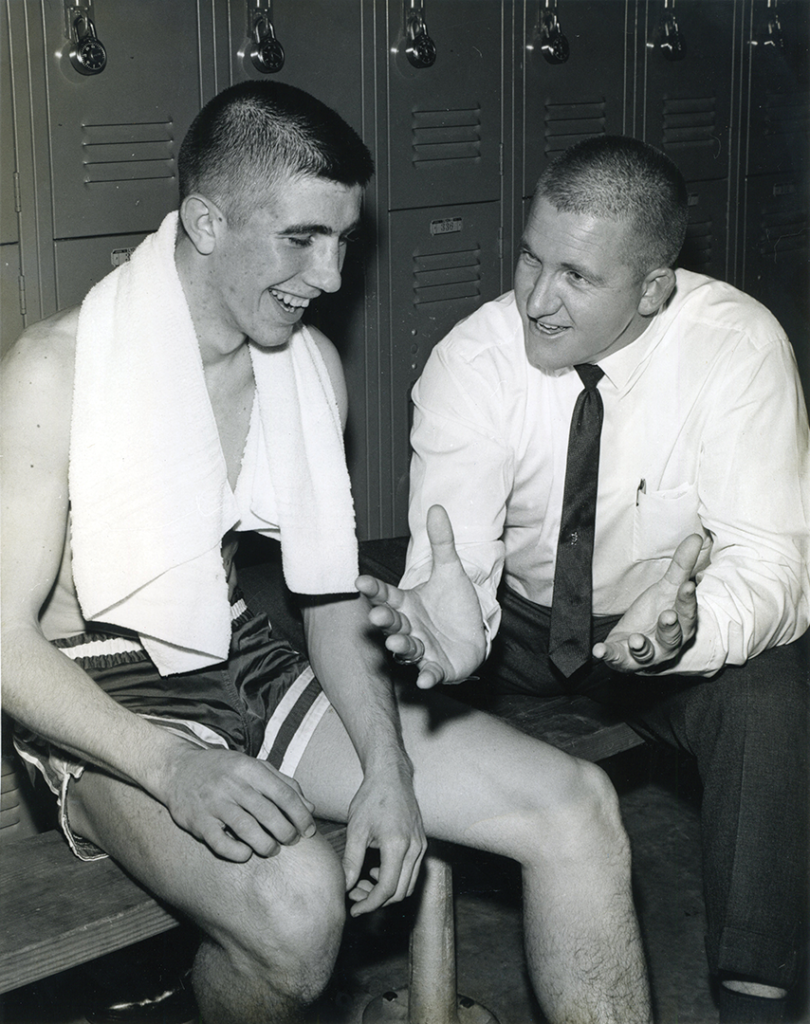

There were the guys in the Amen Corner, too. The “Tip-Off Club Officers,” who were not elected and never met, were among them: Walker Harris, Frank Christian, Herb Vining, Walter Partee and others from time to time. These men supported the community, the basketball team and Bradley, whether they had sons in the program or not. If there was a need, it was met. They sent the team on the road in chartered motor coaches. They fed the players after every away game. They put them up in hotels for tournaments. It was not uncommon to see the Newton Rams, dressed in matching blue blazers, gray slacks, white shirts and blue strip ties—all shorn in similar crew cuts—dining at the finest restaurants in Atlanta, like the Brothers Two, the Marriott Fairfield Restaurant and the J-BAR-D Steakhouse, or chowing down at The Varsity.

“If you put your effort and concentration into playing to your potential, to be the best that you can be, I don’t care what the scoreboard says at the end of the game, in my book, we’re gonna be winners.”

Coach Norman Dale, “Hoosiers”

If Bradley’s team had a particularly good year, it might warrant a new station wagon for the coach. If the team had performed well over the course of the season—and it always did—the players were feted with barbecues and steak dinners and trips to places like the Sweet 16 high school tournament in Kentucky. If a player couldn’t afford the team blazer or dress shoes to go with it, they were provided, as were letter jackets and a new pair of Converse All-Stars each season. The players were special, and they were treated special.

It all started when then-Newton County High School Principal Homer Sharp persuaded Bradley, a former Avondale High School and University of Georgia star athlete, to leave his job with the Ft. Lauderdale Recreation Department in Florida and move his family—which at the time consisted of his wife and high school sweetheart, Jan Thomas Bradley, and infant daughter Brenda—to Newton County and accept a job teaching physical education and coaching boys’ basketball. That was 1957. Mickey Mantle was in the process of winning the MVP in the American League, and the Detroit Lions won the NFL Championship. There would not be a Super Bowl for another 10 years.

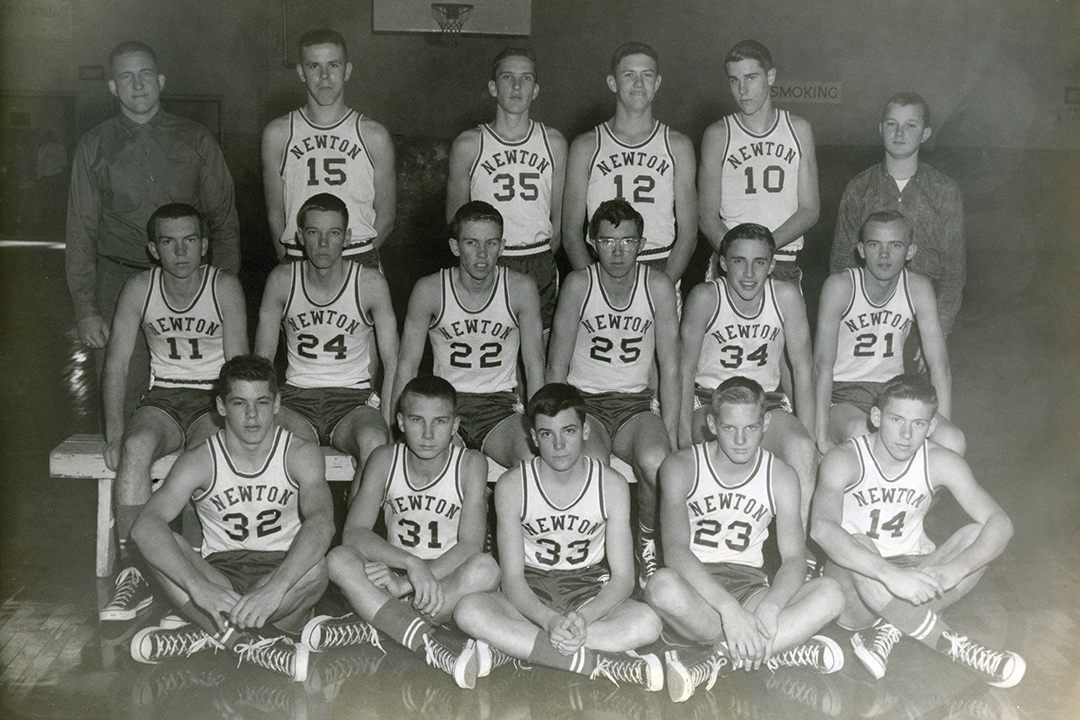

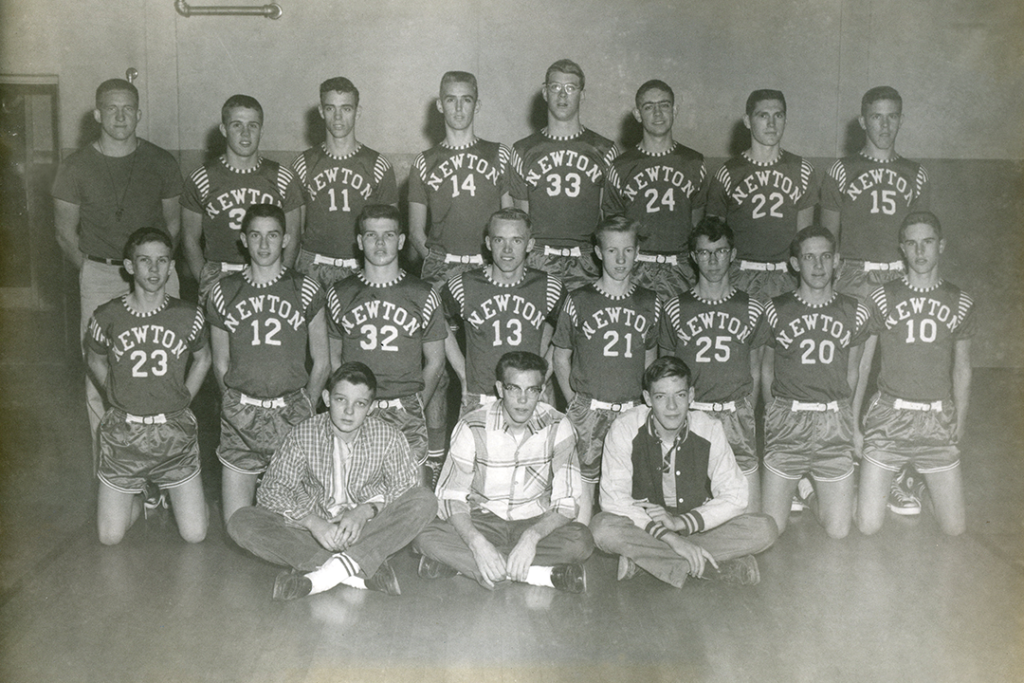

Bradley inherited a team that was full of athletic talent and loved to play. Led by Porterdale’s Billy Dean Rutledge, the first edition of Bradley’s Boys won their first 18 games, immediately capturing the hearts of the whole county. They finished the season 24-3, losing a controversial game to Gainesville in the region semifinals, where a win would have sent them to the state tournament for the first time in school history. Rutledge averaged more than 20 points per game and was the darling of the community. He became the first Newton player named to the North-South Georgia All-Star team but tragically drowned before getting to play in the game. Thousands attended his funeral in the Porterdale Gym that summer. A love affair with basketball was born, and it continued for a generation.

Bradley’s teams followed that first successful season with records of 21-5, 29-1, 27-4 and 29-3. Led by All-American Tim Christian and All-State players Stan Harris and Wayne Hall, the Rams went 35-1 and defeated Hart County to win the Class AA State Tournament in 1964. The only blemish on their record came in the last game of the regular season against Winder-Barrow—a game in which Winder fans were told to arrive at the school at noon to fill up their small gym and prevent any Newton supporters from gaining admission. Association-assigned officials were sent home, and local referees called the game. Christian was saddled with his first foul on the opening tip of the game, his fourth foul on the opening tip of the second half and played less than 10 total minutes before fouling out. Newton beat Winder by 17 in the region tournament the next week, and Christian scored what was then a school-record 42 points. The Rams went 35-1 the following season, losing only to Sandy Springs in the state semifinals.

By now, Rams fever was at full epidemic stage. They were in the midst of their national-record 129-game homecourt winning streak, and every game was a sellout. If a good team came to town, people lined up in the wee hours of the morning for a 7 p.m. girls’ game. Some 3,200 people crowded into a gymnasium built to hold 1,850, and folks leaned extension ladders against the side of the building and peered through the windows—on 20-degree nights—to try and catch a glimpse of the action inside.

Visiting teams, trying to avoid being psyched out by the enormous crowds, arrived dressed to play and sat on the bus until game time or came into the gym and went straight to the dressing room under the visiting stands to escape the earth-shattering cries of “Ram Bait!” as they walked. The cries often became so loud that the girls’ game had to be stopped when the visitors ambled around to get dressed and again when the home team, decked out in the blue blazers and ties, made the march to its dressing quarters.

The crescendos during the games themselves were even louder. Bradley for years had a framed photograph of a game against Burney Harris, the first all-black team to play in “Death Valley,” hanging on his office wall. The gym was packed, with fans standing three-deep around the court. Burney was playing a zone defense, and all five players had both hands covering their ears.

When an opposing player fouled, cries of “You! You! You!” rained down upon him, and when an opposing player toed the free throw line, the noise from Newton fans stomping their feet on the wooden bleachers was deafening. Newton players were in great shape. Opposing players could not always say the same. If the gym was a little warmer than most, it worked to the home team’s advantage by the fourth quarter.

When the game was out of reach and victory assured, Mrs. Pearl stood up and put on her gloves, and someone—Mike Lassiter for many years—unfurled a sign across the entire student-section side of the gym that declared, “Death Valley, 1 (and however many) straight.” There was always a subscript: “We love Bradley”

We did, too, and we still do: 17 years, 400 wins, 68 losses, 14 region championships, one state title. That was a pretty good start to a career that saw Bradley win 1,372 high school basketball games and get elected to the National High School Hall of Fame. He returned to Newton County “after his retirement” and coached four more years, as he won another 74 games and took his final Newton team to the Final Four in 2005. He then turned over the reins to assistant Rick Rasmussen, who remains the coach and maintains Newton as one of the state’s top programs, year in and year out.

As for the magic? Well, I don’t talk about it much anymore, because if you weren’t there, you wouldn’t believe it.

Click here to read more stories by Darrell Huckaby.

1 comment

Why don’t they make a movie and use Sharp gym to film it?