Sherrod Smith was immortalized as a central figure in one of Major League Baseball’s all-time dramas, as he went pitch for pitch with Babe Ruth in Game 2 of the 1916 World Series. More than a century later, his performance on an October day in Boston still echoes through the ages.

Erected in 1994 and tucked away on a non-descript stretch of Highway 11, Georgia Historic Marker 107-10 honors the life and career of “Mansfield’s Famous Southpaw.”

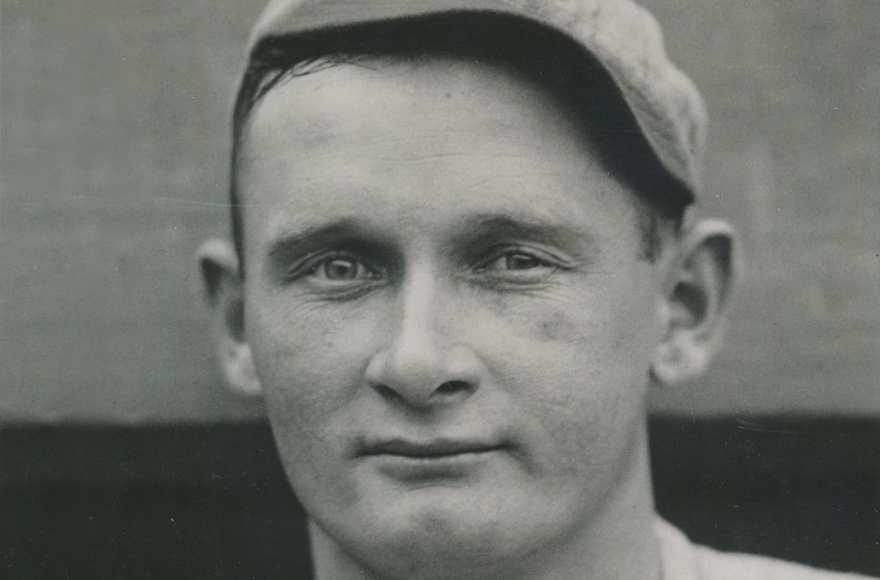

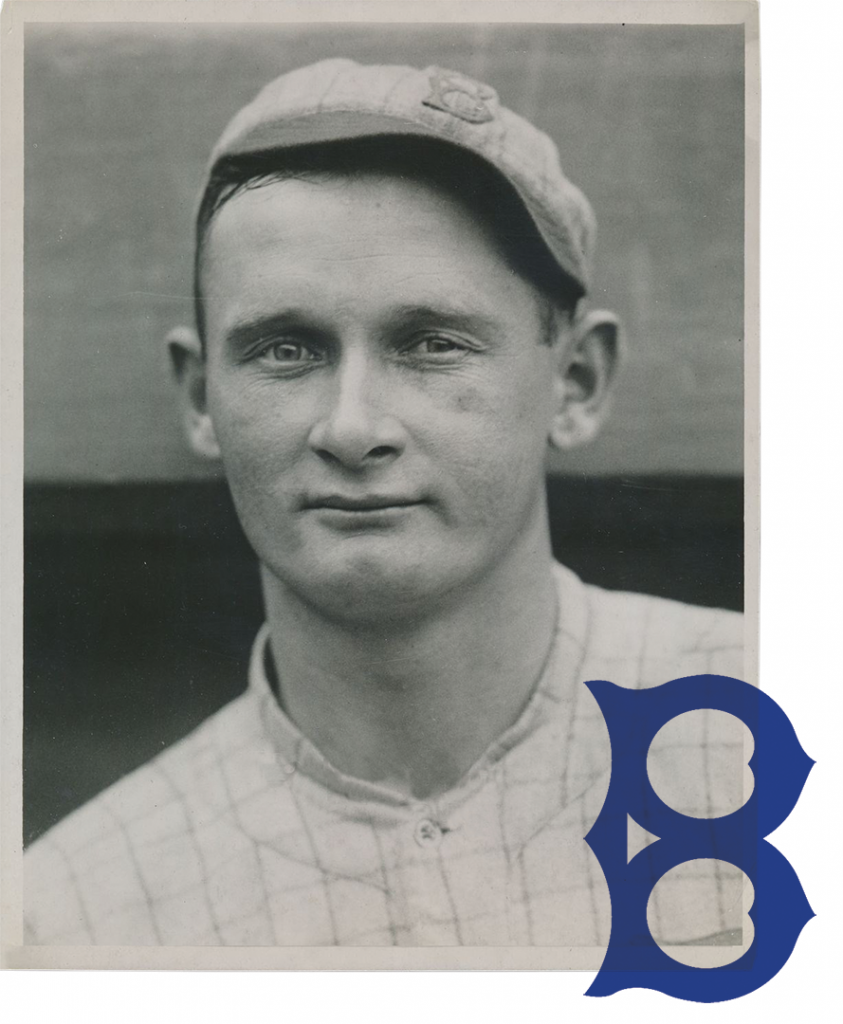

Sherrod Malone “Sherry” Smith was born in Monticello near the end of the 19th century and had a talent for throwing a baseball. The 6-foot-1, 170-pound left-hander honed his craft as a pitcher with semi-pro teams in small towns before he joined the Pittsburgh Pirates as a baby-faced 20-year-old in 1911. Smith appeared in only four games in his two seasons with the Honus Wagner-led Pirates, but he went on to play 12 more years in the major leagues—his career was interrupted briefly by his military service in the United States Army during World War I—with the Brooklyn Robins and the Cleveland Indians.

A cursory glance at Smith’s resume reveals little about the place he carved out for himself in baseball history. He finished his career with a sub-.500 record (114–118) and a solid-but-unspectacular 3.32 earned run average, striking out 428 batters across his 2,052 and two-thirds innings of work. Known for his deceptive pickoff move and the consistency with which he stifled opposing base stealers, Smith enjoyed his best individual season in 1915, when he went 14–8 with a 2.59 ERA and pitched two shutouts while in rotation for the Robins. Nothing jumps off the page, at least initially.

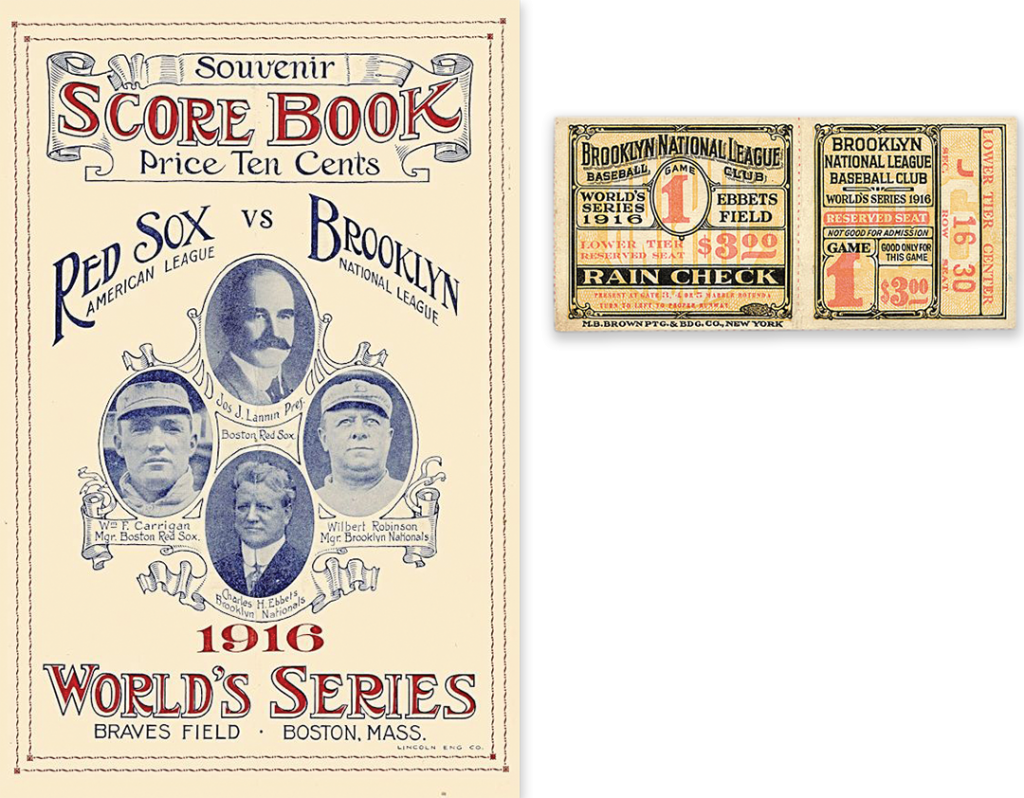

However, Smith made an enduring mark in the 1916 World Series, three years before the Black Sox Scandal shook baseball to its core. He toed the rubber for Brooklyn in Game 2, his team having fallen behind the Boston Red Sox in the series two days earlier. Smith was not the original starter—that task was supposed to fall on Jack Coombs—but Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson played a hunch and instead called upon the soft-tossing lefty. Opposing him on the mound was a 21-year-old Baltimore native who would soon grow into a larger-than-life cultural icon: George Herman Ruth. Known more for his craftiness as a pitcher than his talent as a hitter, Ruth had only swatted seven of his 714 career home runs by the time the 1916 season was complete. He was not yet “The Babe.”

“It’s hard to beat a person who never gives up.”

Babe Ruth

Nearly 50,000 fans filed through the turnstiles at Braves Field in Boston on Oct. 9, 1916. Autumn was in the afternoon air, a sense of anticipation rippling across the park. Ruth entered his first World Series start on the heels of a remarkable regular season during which he had compiled a 23–12 record and led the American League in ERA (1.75), starts (40) and shutouts (nine). He was the unquestioned main event. To the surprise of almost everyone in attendance, Smith matched him pitch for pitch for 13 innings. Tied 1–1 in the bottom of the 14th, Boston broke the dam. Smith issued a leadoff walk to Dick Hoblitzell, who advanced to second base on a sacrifice bunt from Duffy Lewis. After Mike McNally was inserted as a pinch runner, Del Gainer delivered a one-out single to left field to score the game-winning run. More than a century later, it remains one of the most memorable pitching duels in World Series history. It was Smith’s only appearance in the 1916 series, which Boston won in five games.

John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball, chronicled Smith’s efforts on Our Game, his MLB-hosted blog, in October 2018. The post was titled “When the Babe Played Second Fiddle” and shed renewed light on an overshadowed figure.

“History credits this as one of [Ruth’s] greatest pitching feats in one of the greatest seasons any pitcher ever had, but reporters covering the game were far less generous,” Thorn wrote. “In their telling, Sherry Smith was the story.”

Smith returned to the World Series with Brooklyn in 1920, and he was stellar in two starts against the Cleveland Indians—a team spearheaded by the great Tris Speaker. He fired a three-hitter in a 2–1 victory in Game 3, but he was outpitched by Duster Mails in the decisive sixth game, as the Robins fell 1–0 and ultimately lost the series. Though his best days were behind him, Smith continued on for seven more seasons and even led the American League in complete games (22) in 1925.

Once he left baseball behind, Smith enjoyed a second iteration as a law enforcement officer and became the chief of police in Porterdale and Madison. He died at the age of 58 on Sept. 12, 1949 and was buried in Carmel Church Cemetery in Mansfield. Smith was posthumously inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1980, his accomplishments resonating decades after his death. His 0.89 career ERA in the World Series still ranks fourth on the all-time list for pitchers who have pitched a minimum of 30 innings in the Fall Classic, bested only by Madison Bumgarner (0.25), Harry Brecheen (0.83) and the aforementioned Ruth (0.87).

Click here to read more stories by Brian Knapp.