The Labor Day shooting incident involving Covington police officer Matt Cooper spurred the implementation of a potentially life-saving Stop the Bleed training program at Piedmont Newton Hospital.

So much in life falls outside of our control. Bad things happen, from terrorist acts in our cities to gun violence in our schools, places of worship and movie theaters. It has become an all too familiar refrain, and if man’s inhumanity toward man were not enough, it seems that humans are prone to injuring themselves, through accidents at work or play, at home or on the highways.

Most of the time, we are neither victims of nor witnesses to such crimes or accidents. If we were, would we know what to do? If we or someone else lay bleeding and in danger of losing his or her life, would we know how to save it? Preventing a calamity may be out of our control, but knowing how to respond to one could be within our reach.

Perhaps nowhere is that need to know greater than with law enforcement personnel, often the first to arrive on a critical incident scene, such as a shooting or auto accident. Until recently, the medical training for Newton County law enforcement had been largely limited to basic first aid. However, the Labor Day shooting incident involving Covington police officer Matt Cooper served as a catalyst for change.

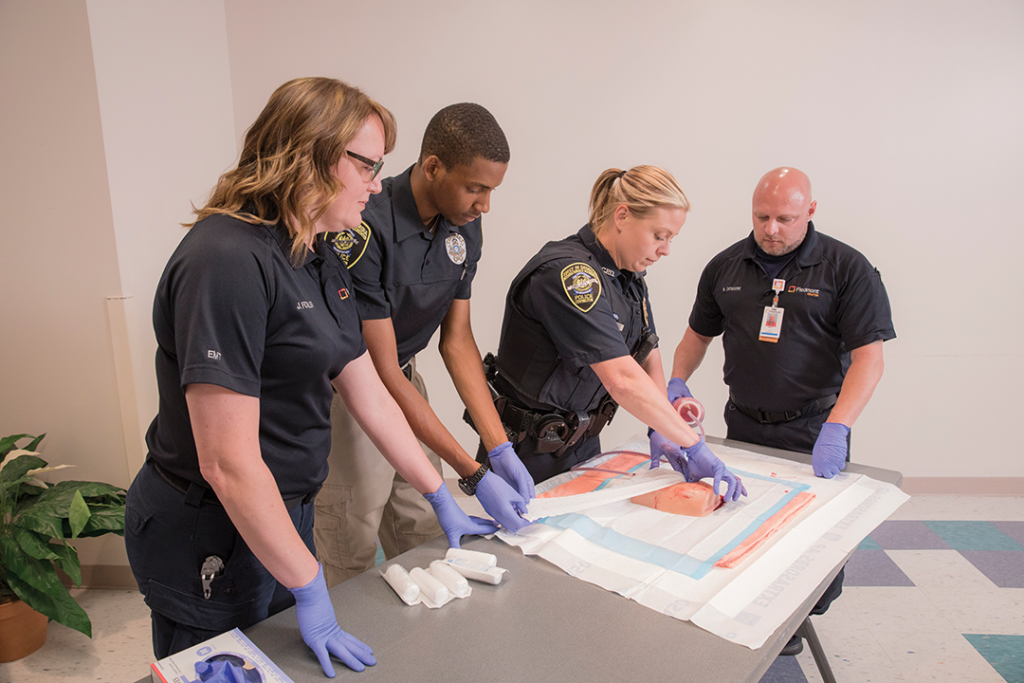

“It was what got them thinking and saying, ‘Hey, we need more [training],’” said Jan Fowler, an EMT at Piedmont Newton Hospital and the regional coordinator for the Stop the Bleed program, a national effort to train the public in preventing death by uncontrolled bleeding. “It’s a nationwide initiative. Basically, after the Sandy Hook [Elementary School] shooting, a group of doctors got together and they did some research and they found that uncontrolled bleeding is the number one cause of preventable death from trauma, so they decided to create a program to teach regular people—not medical people, but regular people—how to stop hemorrhaging.”

“We’re not paid to be here. All of the instructors are volunteers. They do it on their own time, because they really want to make a difference.”

Stop the Bleed Regional Coordinator Jan Fowler

Before coming to Piedmont Newton, Fowler worked for several years in the Macon area and taught STB in schools, churches, courthouses and businesses throughout Region 5, an EMS designation for several counties lying below I-20. Two years ago, Newton became the first county in Region 3—an area stretching from DeKalb County to Newton—to get STB, as all county schools received the training. The plan now is to train every law enforcement officer in the county. Classes started in April and are scheduled to run through October. Approximately 156 sheriff’s deputies and 60 Covington police officers are slated to participate, along with additional officers from Porterdale and Oxford. Fowler indicated that several Georgia State Patrol posts, as well as game wardens, have also expressed interest.

STB trainer Trey Phillips works as a flight nurse and a paramedic with Piedmont Newton. He relayed the experience of arriving at a scene where appropriate attention to a bleeding victim has not been given.

“As a paramedic and medical provider, there’s nothing more frustrating than racing to a scene—it’s going to take you minutes to get there, at least—[and] nobody’s done anything ’cause nobody’s trained and you have nothing to work with when you get there,” he said. The outcome can be dramatically different for someone who knows how to stop a bleed and takes action, according to Phillips.

The primary issue? Not a lack of compassion, but a lack of know-how.

“I think, as a general rule, people want to help,” STB trainer and paramedic Robert Underwood said. “Maybe they don’t decide to choose this profession, but they still want to help, so if you give them that tool, it gives them the opportunity.”

STB training classes are Power Point-based but also “hands-on,” according to Fowler. Utilizing a STB trauma first aid kit, attendees learn how to wound-pack, as well as apply tourniquets to themselves and others. During one of the training sessions in April, Fowler was joined by co-instructor and EMT Brent DeMark in front of a class of about 60 deputies. The two presented the subject matter in a clear and precise manner but with enough humor mixed in to keep the deputies relaxed and engaged. The trainees were instructed in how to apply the Combat Application Tourniquet to themselves and were warned that the process was accompanied by significant discomfort. Phillips and Underwood moved about the audience while demonstrating proper techniques and making sure they were executed correctly. As CATs tightened around arms and legs, deputies grimaced, grinned and hobbled around in self-inflicted pain.

Trainees also learned that using a tourniquet rarely causes the loss of a limb, allowing them to become comfortable with the idea of using it. Once trained, law enforcement officers will receive their own STB trauma kit containing a tourniquet, gauze and other accessories to carry with them in the field. Under the leadership of CEO Dr. Eric Boer, Piedmont Newton planned to donate approximately $10,000 to purchase the kits.

After they are finished training all the deputies and policemen in the county, Fowler and her team of volunteers will turn their attention to schools who have already requested re-training. Public places like courthouses, businesses and churches would likely be next on the list. Eventually, they hope to make STB as accessible to the community as CPR classes are now.

In the meantime, interested persons can learn more about a limited number of open classes at www.bleedingcontrol.org.

Part of Fowler’s job as the regional Stop the Bleed coordinator involves looking at “line of duty” deaths among first responders across the state. According to Fowler, three deaths in 2018 have been followed by one so far in 2019. She looks at their autopsy reports to determine whether or not their injuries could have been treated with STB techniques and their lives possibly saved. The findings then go into a database to measure the effectiveness of the program.

“For me, it’s very frustrating,” Fowler said. “I’m not there with them, but I’m there, because we have had those instances where I’ve had to look at those reports and go, ‘Yeah, this one might have gone home.’ It is a passion for us. We do it because we don’t want this to happen again.”

Click here to read more stories by David Roten.